While David Crane’s other August release, Fishing Derby, was a unique experience in the gaming space, the same can’t exactly be said for his other Activision debut cartridge. Atari’s first-party releases to this point are predominantly made up of arcade conversions and takes on real world activities, and with today’s game, Dragster, David Crane covered both of those bases for his new company – just with some serial numbers filed off.

Dragster is, at its core, based on the sport of drag racing, where drivers run short straightaway races in incredibly fast cars – often needing parachutes to slow down when the races are finished. Once a popular activity on actual busy streets with modified cars in the mid-20th century, drag racing eventually started moving into dedicated, quarter-mile tracks known as drag strips in the 1950s and even seeing formal racing leagues form up. The oil crisis and subsequent move by auto companies towards less beefy, more fuel-economical cars in the 1970s dramatically shrunk the accessibility and interest in this subgenre of racing, but for game designers and players from that period, it’s not a stretch to imagine that they were aware of its heyday and were interested in ways to relive it. In a 2025 Retro Gamer feature, Crane indicated that growing up in the rural Midwest, the people there (seemingly him included) had an obsession with “souping up” their cars to achieve faster times. This was likely a factor in why he opted to make it one of his first Activision projects.

Unsurprisingly, drag racing would prove to be a good fit for arcade games, not only because driving games were easy to grasp in car-centric societies but because drag racing intentionally allowed for fast sessions. Allied Leisure produced a projector-based release drag racing game in 1971 for two players, and in the era of video games, Electra Games released Eliminator IV, a four-player take in April 1976. Eliminator IV brought with it a gear shift, a component missing from Allied Leisure’s earlier electromechanical game and a key component to a drag race; with little in way of obstacles on the road, being able to manage your gears and acceleration is what truly separated winners and losers. This arcade title may have even been the inspiration for an unreleased four-player drag racing game for the Bally Professional Arcade that appeared in early advertisements. Eliminator IV would not stand alone with the genre in the video game space for long however, as in the summer of 1977 two more takes on the sport would be released.

On the home console front, Fairchild published their Drag Strip cartridge for the Channel F around August 1977. Taking advantage of the console format, Drag Strip allowed players to select what kind of car they wanted to drive – really just changing how they accelerate, their top speeds and how difficult it would be to avoid an engine blowout – and even provided a way to run single-player races by having an option that immediately has the second car stall out. The Channel F’s unusual controller worked very well at simulating the necessary controls for a drag racer. Acceleration is handled by twisting the controller knob, and shifting gears involved simply moving the knob into one of the four cardinal corners of its square movement space, not unlike an actual shifter. Whoever the unknown developer on this cartridge was, they did a good job of translating these races to the limited hardware.

Over on the arcade front though, Atari published Drag Race circa June 1977, and looking at it you can immediately tell that this is where David Crane got his inspiration. Dragster is as close to a conversion of Drag Race as you can get on the VCS hardware. The arcade game is a two-player race, with gear shifting and a little bit of steering to prevent your vehicle from veering off the straightaway into the grandstands. Developed, programmed and engineered by Mike Albaugh, Paul Mancuso, Howard Van Jepmond and Barney Huang, the game gives players a few heats to race against one another – as well as their best times – before calling it a day. In his interview with Scott Stilphen, Albaugh remarked that he hadn’t paid attention to drag racing since around 1968, and therefore had missed a few changes to the sport in the years since then, notably the location of the engine on the car, which had since moved behind the driver for safety reasons, and the number of starting lights. He ensured the light made a booping sound loud enough to hear over the engine noise. It was a minor success for Atari, as RePlay magazine notes that it was the fourth “hottest game” from their November 1977 edition, and around 1,900 units were sold based on an internal Atari coin-op production memo. Compare this arcade game to Crane’s take on the VCS, which features a two-player race between drivers with the exact same visual perspective, gear shifting, and on the harder difficulty, the need to steer your car so you don’t careen into the stands. Unsurprisingly, Atari named Dragster specifically in its 1980 lawsuit against Activision as infringing on its properties and trade secrets that would ultimately be tossed out a year and a half later. Albaugh, when asked, added that his feelings on Activision’s game were “mixed,” and that he wasn’t really sure why Crane made the same choice regarding the car design.

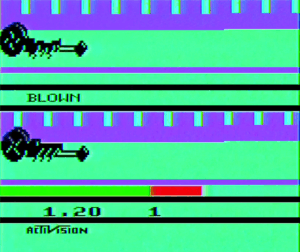

Years after the fact, Crane does not hide the fact that Dragster was based on Drag Race, but said it was a tricky conversion given the limits of the hardware. Having to compress the accelerator, steering wheel and gear shift of the arcade game into the VCS joystick was the most challenging aspect of the design, he explained, and it is actually pretty impressive. The button functions as your accelerator, but for shifting gears the player has to push it left to clutch and letting it go back to neutral to shift up a gear; downshifting isn’t possible. If you’re still accelerating while shifting your car will blow out the engine, as will allowing the green and red bar, your tachometer, fill too far. Crane said he worked on the powertrain simulator for the cars to try and make it feel as realistic as possible as you accelerate and shift. If you choose to play the second game type on the cartridge, the steering functionality from the arcade game is implemented, with your car drifting up and down its lane and the player having to periodically push or pull the stick to keep it on course. While this is a decent enough addition to keep the game interesting, even the default can be plenty engaging just by racing against your own best times.

In comments collected from the Atari 2600 Connection newsletter from 1992, an issue of Retro Gamer from 2008, and on the defunct website Gamegrid, Crane elaborated further on the game’s development, noting that the game owes its existence to new programming techniques that allowed for a high resolution score display that Crane, in turn, was able to convert into the drag cars themselves. As Crane explained, earlier games had large, blocky numbers on either side of the screen to indicate the player 1 and 2 scores. Crane was able to refine this into a six-digit score display by iterating on their work, and from that Crane reworked that technique for his vehicles. He created a high-resolution object from the score display, converted it into graphics and was then able to slide it across the screen. From there, he had to program the rest of the game to move in time with this graphical object, resulting in Dragster. The end result was a sprite object 32 times the size of a tank in Combat but with the same resolution, something the VCS architecture was never expected to support. In Retro Gamer Crane referred to this as “possibly the most advanced piece of display code written for the 2600,” and that while you may have had to be there at the time, the code to keep the game timed so that object moved smoothly was some of the tightest programming he’d achieved on the hardware (though he still felt his later work, Grand Prix, was his favorite). Adding to that from Gamegrid, he went on to state that after the game came out, other developers started using the same technique in their games, presumably after analyzing his code.

Landing a solid time requires very fine reactions and quite a bit of experience on when to pop the clutch, how carefully to manage your tachometer to keep your engine from blowing, and even how best to manage the start of the race to get maximum acceleration as soon as possible. In a battle of milliseconds, every refinement to your technique counts. and thanks to its time trial nature, Dragster has a genuinely compelling play loop whether or not you’re playing it solo or with a friend; racing the clock is about as fun as against another vehicle here. Given how quick races are, Crane wisely allowed you to restart by pressing the controller button, making this the first VCS game to do so and one that is very easy to keep coming back to.

Dragster was seemingly a big hit for Activision, with Crane noting that it sold more than 500,000 copies in its first year and accounted for half of Activision’s total revenues in 1980. These admittedly recollected figures are particularly impressive when you consider that Activision did not have Atari’s distribution network; furthermore, by the end of 1980 there were roughly two million VCS units in people’s homes, seven first-party games that had hit those numbers in lifetime sales, and only Space Invaders surpassing them all at one million units sold.

While the initial review of it in the pages of Video magazine’s Arcade Alley column referred to it as the least of Activision’s initial offerings, Crane relayed an anecdote about an Activision sales rep’s son who told him that he’d been playing the game for 35 hours straight before it had even hit store shelves. With each race lasting only a handful of seconds and the game allowing players to jump right back in with a tap of the controller button, Dragster was the perfect fit for people aiming to try and improve their time, little by little. Other reviews were much more positive; an April 1981 review in Video Action declared it the most challenging of Activision’s early offerings and “great fun” that they’d be replaying again. And Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games edition found it to be a “terrific game” to show off to new players, albeit one that will take multiple attempts to get the hang of.

It’s this high score – or in this case, low time – chase that brings us to the part of Dragster’s legacy where it intersects with the history of competitive video games. Dragster is the first of Activision’s games to offer up a commemorative patch to anyone who could get a time under 6 seconds and sent in a photograph proving it, which would earn you membership in the World Class Dragster Club. At the time of the game’s publication, David Crane’s remarks in the manual note that the world record was 5.61 seconds. When Activision began publishing high score records in their newsletters the following year, 5.61 seconds was indeed held by a father-and-son duo. By the winter 1982 edition, the record had dropped to 5.57 and was held by a trio of players, including teenager Todd Rogers, and a fourth player joined them in the fall. Finally, in December 1982, Activision published a new record of 5.51, noting elsewhere in the newsletter that Rogers had gotten it. He wasn’t the only person to claim this time, according to the spring 1983 edition, but Rogers had been prolific high-scorer at the time in several Activision titles, and would go on to leverage this into a championship player identity in the years after claiming this record. On his personal website Rogers said he was able to beat Activision’s own computer simulated record time of 5.54 by popping the clutch the second the light turned green to start off in second gear. An investigation into the game’s code by computer engineer Eric Koziel found that this was impossible, and even the computer simulation time of 5.54 that Rogers talked about wasn’t doable; 5.57 seconds is indeed the lowest time possible for Dragster; plausibly the polaroid he had submitted to Activision wasn’t clear enough, making the final 7 look like a 1. This discovery ultimately led to Rogers’ scores being invalidated by the high score tracking site Twin Galaxies. Whether or not Rogers was cheating, though, Dragster – alongside other early score chasing games like Asteroids and Space Invaders, was an early pioneer in competitive gaming, and what would eventually morph into both speedrunning and modern esports.

Dragster may indeed be one of the leanest games Activision sold on the VCS, but with a game loop on par with something you’d get out of a mobile game it has held up remarkably well. This isn’t the only time Activision’s developers would take a minor or unreleased Atari arcade property and produce a massively successful VCS take on it – as seen with Bob Whitehead’s Boxing or Larry Kaplan’s Kaboom! in 1981 – but with Dragster you have to admit they were pretty good at it.

Sources:

David Crane, correspondence with the author, August 2017

Mike Albaugh, interview with Scott Stilphen, Ataricompendium.com, 2017

A New Era Begins: Activision Exploits Atari’s Success, Video, December 1980

Prima Facie: Games, T.B. Martin and Alex Josephs, Video Action, April 1981

Atari VCS Games Roundup, Martha Koppin, Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games, December 1983

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, 2016 (unpublished manuscript)

Doubt and Drama Still Haunt an Old, Seemingly Impossible Atari World Record, Heather Alexandra, Kotaku, July 7, 2017

A Man Accused of Cheating at Video Games may lose his Guinness World Record, Amy Wang, Washington Post, Jan. 29, 2018

The Arcs of Atari, Retro Gamer 46, January 2008

A Tribute to Activision: The Atari 2600 Years, Rory Milne, Retro Gamer 268, January 2025

A Conversation with David Crane, Master of the 2600, Tim Duarte, The Atari 2600 Connection, September/October 1992

Activision Designer, Gamegrid.de, 2005, accessed December 2007

Atari internal coin-op production numbers memo, atarigames.com, dated Aug. 31 1999

Bally Videocade Cassette Catalog, 1978

Survey, RePlay, November 1977

Activisions, Fall 1981/Winter 1982/December 1982/Spring 1983

Warner Video Boom, Weekly Television Digest, April 13 1981

Home Invasion, They Create Worlds, Alex Smith, 2020

Release date sources:

Dragster (August 1980): Weekly Television Digest, April 28 1980; New York Daily News, August 22 1980; Winnipeg Free Press, November 22 1980; Asbury Park Press, October 9 1980; Merchandising, June 1980

Drag Strip (August 1977): Naples Daily News, August 30 1977; Channel F News Vol. 1, Issue 1 October 1977; Spokesman Review, December 3 1978; Chicago Tribune, October 12 1977