These days, nearly every racing game published is designed around the player’s viewpoint being either behind the car or in the driver’s seat itself. While Night Driver did not originate this perspective, it without question popularized it both in arcades and in Atari’s home conversion.

Yes, Night Driver is a return to the realm of first-party arcade conversions for Atari – something not seen since March 1979’s Canyon Bomber and Sky Diver ports. The VCS version is based off of the October 1976 arcade game of the same name, then nearly four years old by this point. But the technical marvel that was arcade Night Driver and its fast paced, first-person perspective is no less impressive in the scaled down VCS port, as a machine designed to play versions of Tank and Pong is once again pushed to new ground. But that same arcade game has something of a sordid history, as Atari and two of its arcade competitors practically lifted it wholesale from a German arcade game, Nürburgring 1.

Nürburgring 1 was developed and more or less released in 1975 by Dr. Reiner Foerst, who had developed it not so much as a game but as a driving simulation using the TTL technology found in Pong cabinets at the time. Foerst was interested in early driving simulators but was frustrated at the expense, as they were built around computers either putting the image through a projector or an oscilloscope. After Pong became a hit, Foerst recognized that he could make a cost-effective coin-op version incorporating the circuit board and monitor arrangement from arcade machines. The cabinet included all the things you’d expect from a driving sim – a wheel, pedals, a shifter, a speedometer, a mileage gauge. Crashes would be counted and the player would get hit with a timer penalty; the game would end if players either finished the course or when the timer ran out. Foerst had two cabinets finished in 1975 and had them on the show floor at the International Exhibition for Coin-Op Games in West Berlin the following March. There was interest in what he’d designed, but since Foerst didn’t have the money to fund production beyond one unit a week, other companies decided to copy what he was doing rather than wait on his glacial pace.

One of the first companies to do so was Digital Games, known shortly after as Micronetics. Digital Games was a small player in the arcade realm. One of their engineers, Ted Michon, had been sent to West Germany to fix a defective shipment of the company’s game Air Combat when he happened across a Nürburgring 1 machine – by chance, at the same time Foerst was there giving a demonstration to his kids while on vacation. Michon was able to learn how the machine worked and tried to advise Foerst that while his company would be very interested in his game, it was not economically reproducible and would need to be reworked, which he told historian Keith Smith Foerst seemed unbothered by, confident that another US company would license his work as-is. Foerst remembered Michon calling his boss and then abruptly ending the conversation with apparent frustration. When Michon returned to the US he was able to develop a digital version of the game of his own that swapped out the TTL boards for MSI logic chips and PROM chips to store data, coming up with logarithms and antilogs to get the game to function without the benefit of a microprocessor.

Given Digital Games/Micronetics’ weak position in the market and financial struggles, its owners decided to license the game to Midway for a simultaneous release, which in turn farmed it out to development studio Dave Nutting Associates, a frequent collaborator with Midway at the time (to the point Midway would eventually absorb it). Michon told historian Keith Smith that the microprocessor-based hardware system DNA had built didn’t have the power to handle all the calculations needed for perspective changes either, and that he ultimately sent along his optimized tables of logs and antilogs he had computed to help with the implementation. That task fell to developer Jamie Fenton, who remarked to Smith that she did indeed use Michon’s routines to help get the game running within a tight, six-week development window. With the hardware used, Midway’s clone was now running on a microprocessor-based machine that allowed the white rectangles that indicated the sides of the road to scroll smoothly and quickly, and even included a few additional embellishments like a flag-waving referee and an on-screen instrument panel. Midway initially showed it off as Midnite Racer at the Amusement and Music Operators Association show in October 1976 before renaming and shipping their version as 280 Zzzap, after the Datsun 280Z car; the company had licensed the vehicle for a promotion and decided to use the namesake for their game as well. Micronetics published its own version, Night Racer, at the end of the year but closed down soon after.

At Atari, developer Dave Sheppard says he given a piece of paper with a photo of the Nürburgring 1 cabinet, including the picture on the screen. He adds that he never saw the game in action or had any idea how it was designed to be played but was aware that it was German in origin; according to historian Marty Goldberg, Atari had actually licensed out a version from Micronetics’ own unlicensed Night Racer clone and had just provided Sheppard with a minimal amount of information to do its own take. This became Night Driver, a game that had the steering wheel, pedals and gear shift of its German predecessor alongside three different tracks players could choose from. The biggest difference was inside the cabinet, however – where Nürburgring 1 used 28 circuit boards, Atari’s Night Driver had only one with a microprocessor at its heart. This made it much easier and more cost-effective to produce, and Atari ended up selling approximately 2,100 cabinets. The hardware engineers had designed a board where 16 sprites could be placed anywhere on the screen, and Sheppard said these were used for the rectangles that represented reflectors on the side of the road. Observing how fence posts, lamps and signs move while he drove on his commute, Sheppard attempted to simulate the same motion for those little rectangles on screen. These rectangles were all the processor and circuitry needed to deal with, too – instead of drawing a car graphic on screen, Atari simply placed a decal on the screen of your vehicle’s hood. According to Sheppard, this was an extremely popular game within the company, with a steady stream of people coming through Sheppard’s lab to see it in action – something he said was a distraction that cost him development time.

This all undercut Foerst. Back when Michon met him, he had been working on getting his game officially licensed in the US for production, and as Michon told him, the 28-circuit board setup was making production difficult. Once Midway and Atari published their own clones, he saw many of his orders canceled. Michon would write him a letter explaining what was happening with his game stateside, and Trakus, the company that initially produced Nurburgring 1, even sued Atari over their clone. Foerst, undeterred, would found his own company and continued to work on follow-ups to his initial game, including one called Nürburgring Power Slide that had an early example of physical feedback to the game – the player’s cockpit area would tilt back and forth based on what was happening on screen – and Nürburgring Competition, which had fully linked up cabinets. Overall, however, while 280 Zzzap, Night Racer and Nürburgring 1 are all fairly obscure, minor footnotes in arcade history, Night Driver has retained some recognition over the years. A big part of that may be due to its solid home conversion on the VCS, which was by mid-1980 rapidly growing a relatively sizable consumer base off the strength of Space Invaders.

The VCS actually hadn’t seen any kind of racing game since its 1977 launch, when it came out alongside Indy 500 and Street Racer. Both of these games were unique takes on the racing premise, and similarly Night Driver is just as different. This was developer Rob Fulop’s first game on the VCS, having started off doing sound effects for Atari’s Superman pinball machine as a summer job before being hired on for the home division after graduating college the following year. In interviews, Fulop said he’d started programming in high school, writing simple BASIC games like a Nim clone called Takeaway, and a “Boy Analyzer” that would write out how good a boyfriend someone with a specific name would be. After coming to the home division, he was given a bare-bones manual for how the VCS worked and unfettered access to Atari’s arcade demo room. Fulop explained that, when starting out, he felt like he couldn’t necessarily make a video game. As such, all of Fulop’s games written while at Atari would be conversions of existing titles with varying degrees of fidelity and accuracy, such as his rather different Atari 8-bit computer version of Space Invaders. After six weeks, he decided he could get a version of Night Driver working on the home console, and with a lesson on getting the display working on the VCS from Larry Kaplan, Fulop got underway.As an aside, Kaplan told me in our correspondence that Street Racer had initially been intended to be a version of Night Driver, but as someone else had “called dibs” he reworked his concept into that first-wave VCS title. While unclear who that someone else may have been, his assistance with Fulop’s game is a bit of a linkage between that early interest from Kaplan and what we ultimately got.

Given his tenure with the coin-op department and friendships with the staff there, Fulop has mentioned in interviews that he had access to their labs, which he found “extraordinarily useful” when converting games to the home. Such appears to be the case here.

In comments on my original YouTube video for this game, Sheppard remarked that he provided Fulop with the source code to the arcade Night Driver and tried to explain, with some difficulty, how it worked to him. Even though both machines had a 6502 microprocessor at their core, Sheppard said, the VCS was much more constrained; while the arcade game could calculate the positions of all 16 reflectors on screen within two milliseconds, the VCS needed to calculate everything on screen within that same time frame. Ultimately, he added, he didn’t know if Fulop was able to make use of any of the materials he provided.

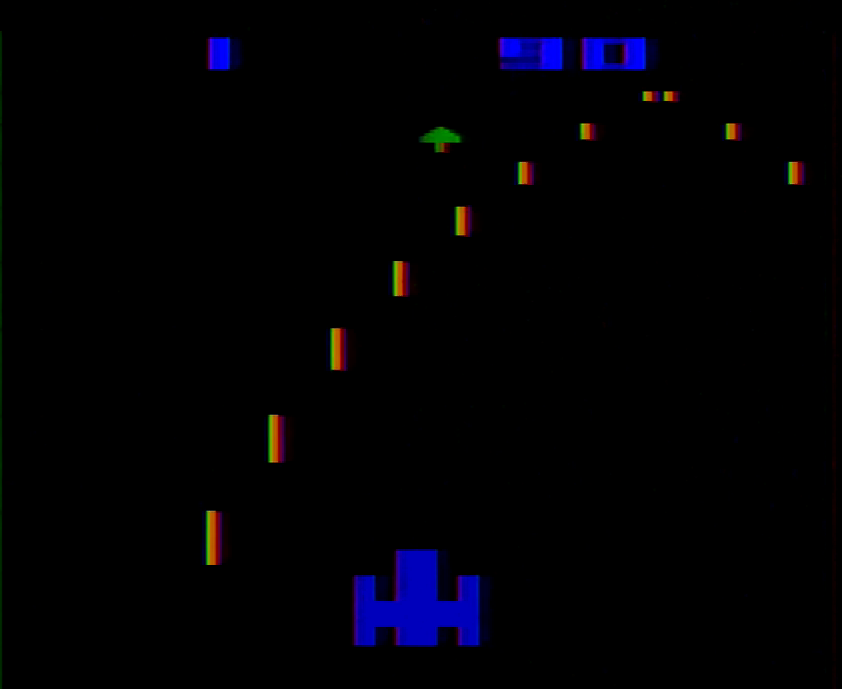

Owing to the differences in hardware, Fulop made several changes – arguably for the better. As the game used paddle controllers, the gear shift had to be removed entirely. The car now accelerates quickly to its top speed, which can be adjusted by flipping the right difficulty switch. If you’ve got your system set up appropriately, one could even use that difficulty switch as a de facto gear shift. The road is more crowded now, too, with other cars showing up that you must dodge – the left difficulty switch adjust whether or not you get a heads up honk as they approach. The game also features little embellishments not seen in the arcade game, such as houses and trees alongside the road. Despite these changes, the base premise is still largely the same – the player has a set amount of time to travel as far as they can on one of three set courses, or on a randomly generated course. Each collision will immediately halt your car and force you to get moving again – in turn costing you points. And much like the arcade game, the display is incredibly stark – besides the cars and houses, about the only visual cues on screen are the reflector lights alongside the edge of the road. Courses can also be tackled without a timer in some game variations – effectively these are practice modes that allow the player to get familiar with the courses and the game itself.

While it lacks the gear shifting complexity of the arcade game, this home version of Night Driver is a solid title. It’s fast, the driving action is smooth, and the paddle works perfectly as the steering wheel. There’s a learning curve on taking turns, and sometimes the other cars will pop up at inopportune times to avoid a collision, but on the whole this is a fine take on Sheppard’s original. Prior to Night Driver, the only VCS game to use this same perspective – more or less – is the 1977 release Star Ship. Comparing the two allows one to really see an advancement of visual fidelity in VCS development. Bob Whitehead’s game has simple, one-color sprites that grow in size as one approaches them. Night Driver has the same size changes as the driver moves along the road, but the cars and houses have significantly more detail to them than Star Ship’s alien craft. There’s a lot of flicker, but with the speed of the game and the short periods of time anything other than your car is in one spot, it’s not that big a deal.

Fulop said near the end of development, the folks from marketing came over to check out the game he had written. Fulop said that one of the marketing executives asked him where he had gotten the idea for the game, seemingly not realizing that they had already done an arcade original by the same name. The shipped game includes a minor bug that causes the screen to blank out if the player turns all the way left and then does a hard right turn all the way on certain parts of the track – something Fulop remarked only seems to bother him.

Bally-Midway would bring a home version of their 280 Zzzap arcade game to the Bally Professional Arcade, also developed by Fenton, who remarked in an interview with me that the similarity of the Professional Arcade hardware to what DNA used for its microprocessor arcade games allowed the developers to use the logic written for the original This version plays much more closely to its arcade namesake and the arcade version of Night Driver – while it still doesn’t have gear shifting, the paddle knob on the controller allows for fine driving adjustments much like its VCS cousin. The road has no obstacles or embellishments like Fulop’s title does, and you really realize how much they add to the game when you see a take without them. 280 Zzzap also only has the one track, which limits how much there is to do in it. To compensate, the cartridge does include a second game, Dodgem, that has you dodging other cars to reach a finish line, similar to Atari’s Street Racer, or RCA’s Freeway game on the Studio II. In fairness to Fenton’s home version, 280 Zzzap did come out in 1978, two years before the VCS conversion of Night Driver, and there literally was nothing on home consoles like its main attraction at the time.

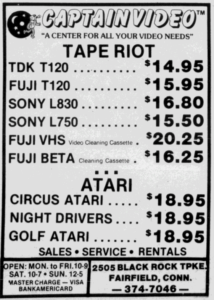

And both Night Driver and 280 Zzzap were thought of rather highly at the time and even for a few years after. In the Arcade Alley column from the January 1981 Video magazine, Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz raved about Night Driver. They referred to the game’s use of simple white lines to define the road as ingenious, and gushed about the additions Fulop added to the game. Arcade racing game fans, they wrote, will be glued to this one. They revisit the game in the pages of Electronic Games magazine from July 1982 in the midst of a roundup of racing games, noting that both Night Driver and 280 Zzzap have excellent graphics and are “true” driving games due to their perspectives. Creative Computing also had a cursory review of Atari’s game in their September 1981 issue, saying only that it is a home version of the popular arcade game and that some people love it, and others hate it.

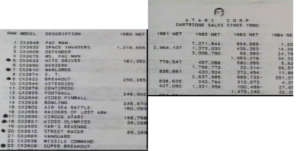

Thankfully, this is one VCS game where you can suss out some internal sales figures early on in its life, thanks to a screen grab of an internal net sales sheet from the Once Upon Atari documentary that was owned by the late Jerome Domurat. While portions of the document are cut off, it suggests that Night Driver was Atari’s fifth-best selling title up to an unknown year – bested by Pac-Man, Space Invaders, Defender and Ms. Pac-Man. Night Driver sold over 161,000 units in its first year, with another 779,000 in 1981, 457,000 in 1982, nearly 581,000 in 1983 and while it’s cut off a bit, it looks like around 5,000 were sold in 1984. Given that no post-1984 releases appear on the visible pages, it’s likely that this document doesn’t include any of the new games released in the Atari Corporation years and likely cuts off either at 1984 or 1985. With our usual late 80s internal sales figures rescued by the late Curt Vendel, we can continue this sales trail along with 84 copies in 1986, just over 7,200 copies in 1987, and over 4,400 copies in 1988. Not counting any sales from 1985, which are still unaccounted for, and assuming the 1984 net sales were in the positives, the game sold about 1,996,268 copies in all, which is frankly impressive for a conversion of such a minimalist arcade game.

With Fulop’s Night Driver proving that these first-person or behind-the-vehicle perspective racing games work pretty well on the VCS, a few more would appear in the years to come, including Atari’s Pole Position conversion, Activision’s Enduro, and Coleco’s unreleased VCS take on Sega’s arcade game Turbo. Night Driver set a fresh standard for VCS driving games, and proved that rookies can still take first place.

Sources:

The (Pre) History of Night Driver, Part 1: Nurburgring, Keith Smith, June 2 2014, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com

The (Pre) History of Night Driver, Part 2: Night Racer, Keith Smith, June 7, 2014, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com

The (Pre) History of Night Driver, Part 5: 280 Zzzap, Keith Smith, July 25 2014, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com

The (Pre) History of Night Driver, Part 6: Night Driver, Keith Smith, July 31, 2014, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com

Dave Sheppard, comment on Atari Archive Night Driver video

Larry Kaplan, interview with the author, August 11 2017-August 17 2017

Once Upon Atari, Howard Scott Warshaw, 2003

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

Jamie Fenton, interview with the author, December 2 2020

An Interview with Atari 2600 developer and Imagic Co-Founder Rob Fulop, Paleotronic, March 29 2019

Rob Fulop, interview with Scott Stilphen, 1993/2000, ataricompendium.com

Arcade Alley, Video, January 1981

Electronic Games, July 1982

Creative Computing, September 1981

Release date sources:

Night Driver (July 1980) – Source: Chicago Heights Star, June 29 1980; New York Daily News, July 31, 1980; Post Crescent, July 31 1980; Westport News, July 25 1980

280 Zzzap (January 1978) – Source: March 15 1978 Ernest Sams letter to JS&A; Merchandising, June 1977; Baltimore Sun, November 5 1978

Antonio Borba says:

What an amazing article….. wonderful, thanx for writing it. I was researching about Night Driver arcade cabinet.