Since Space Invaders kicked off the 1980 lineup of VCS games, it’s clear that this is the year that the platform as we know it today truly started to take shape. It’s the year that the VCS became a monster commercial success and pulled the home console market out from a small niche and into what would become a billion-dollar industry, but while Space Invaders had a big role in that, so too did the rise of third party publishers.

The idea of a “third party,” or a company besides the manufacturer publishing programs, existed in the realm of computers for years at this point. Small publishers had been selling programs for microcomputers such as the Apple II for some time by 1980, and even further back companies like RCA had published programs for IBM minicomputers. You could even make the case that open-source, freely available games and programs that date back to the 1960s were a precursor to the concept of a “third party” publisher popularized in the mid-’70s by companies like Microsoft. But the home video game market was a “walled garden” in the 1970s: the only companies producing games for a platform were the same companies that had made the hardware. If you owned a VCS, you had to choose from Atari’s games. If you bought an MP1000, you were limited to what APF was publishing. The only real exception was Bally’s BASIC cart for the Professional Arcade, which allowed people to write their own programs and make code listings or cassette tapes available for sale, but even this was, by 1980, primarily a hobbyist pursuit and quite niche. But in July of that year, the company Activision published its first four games for a game console they didn’t make or own: Fishing Derby, Boxing, Dragster, and Checkers. In the process Activision set the game industry down a path where today third party publishers and developers make up the vast majority of what’s out there.

Activision didn’t just come out of the blue, however. The company’s genesis stems on one side from four disgruntled Atari software developers – David Crane, Bob Whitehead, Larry Kaplan and Alan Miller – deciding to strike out on their own. If those names sound familiar, it’s because the foursome were among Atari’s earliest game developers, and were known among the software team as the folks who could really make the hardware sing; games such as Canyon Bomber, Basketball, Football and Air Sea Battle all came from those men. The foursome were frustrated with the pay scales they were getting despite the successes of their games – Atari had noted that 60% of cartridge sales in 1978 had come from their games – a lack of recognition externally, due to Atari’s fear they may be poached, and a general restructuring of the home software development group were also factors. Miller put together a compensation proposal akin to those in the recording and book industries that would see programmers get recognition for their work and royalties, but this was shot down by Atari CEO Ray Kassar.

Through a startup law firm, Miller met up with Jim Levy, a marketing executive interested in creating a software company. Levy had his own history with the the computer software business; in the 1970s, he had served as vice president of business affairs at General Recorded Tape Corporation, or GRT. GRT got its start producing music cassette tapes in the 1960s, at a time when record companies were largely focused on vinyl and were all too happy to license out production of cassette-format versions of these albums and singles. GRT eventually expanded its operations to include a record labels and, by the mid-’70s, computer games and programs – a move championed by Levy. Computer programs required more precision during duplication compared to music, which hurt GRT in this endeavor, but nevertheless it persisted in this market until its bankruptcy, and this was the side of the company Levy led. Indeed, when GRT was on the verge of collapse Levy sought to spin off its software business and even wrote a business plan to do so, but GRT petered out before he could. But clearly software was on his mind, and after meeting with the VCS programmers, he saw a lucrative way back in.

By late July 1979 the five men had determined that they’d produce software for the VCS. As the summer went on the developers began leaving Atari: Kaplan left first that June, with Crane and Miller following in August and Whitehead soon after. Kaplan backed out of this foundational effort to work at a startup doing speech software for the computer company Commodore, but when that was clearly going nowhere he returned to Activision that December. Activision itself incorporated in October, and working with an intellectual property attorney named Aldo Test, Levy pinpointed the areas where Atari might try and sue them: the cartridge design and internal documentation of the VCS. The ex-Atari programmers wisely did not bring any materials with them, and reverse-engineered the platform from the ground up to provide all the legal groundwork they needed to beat Atari in court, if it came up. Crane even constructed for them their own unique development system using a custom-built 6502 computer that plugged into the cartridge slot and hooked up to a PDP-11 computer system. Atari did indeed attempt to sue Activision in May 1980, citing stolen proprietary secrets, but without much of a case, the two companies settled by the end of 1981 with Activision becoming an official Atari licensee.

Activision’s initial four games were all announced in April before debuting at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June 1980, and immediately displayed a unique visual aesthetic to Atari’s internally produced games. All four games featured large sprites and solid animation praised as part of the company’s “cartoony” house style in 1982, and they all feature unique play experiences compared to what had come before. In many ways Fishing Derby exemplifies what would set Activision games apart.

The game box isn’t too unusual compared to Atari’s own game boxes at first glance, but the painterly art seen on first party titles is replaced with an artistic rendition of the game itself, with a description of the game itself on the front and back and David Crane’s name prominently displayed as the author. The box also clearly states that this is to use on a VCS console – this was important given that the concept of a game not by your hardware manufacturer was a new one, and indeed even in print advertisements it was regularly clarified that these were Activision games compatible with Atari systems – something that would continue forward through these early years of third party games.

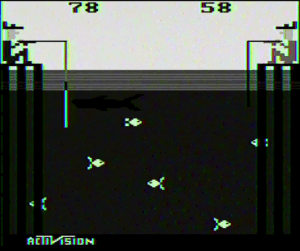

The first thing that jumps out when Fishing Derby itself is loaded up is how colorful the game is. The large background sprites representing the anglers come in multiple colors – the most human any person has looked in a VCS game outside of John Dunn’s Superman – the water is a bold blue, and the sky the color of a sunrise, instantly placing this game at a moment of real time. The fish are all made up of bright, smoothly animating sprites underneath color-cycling waves and a fast moving, hungry shark. The fishing poles move oddly but with a smooth motion that really hasn’t been seen in any VCS game up to this point. And to top it all off is the Activision logo in the corner, boldly stating this game’s origin and providing one final bit of marketing oomph. And the game itself is completely unlikely anything else not just on the VCS, but on the market period.

David Crane said that Fishing Derby started life as a basic aquarium simulator. The sky, the water and horizontal bands of goldfish swimming around were there from the beginning, and while it was visually interesting and regularly mesmerized people from sales and marketing, there wasn’t much of game to it. Crane felt the scoring aspect where deeper fish would be worth more points was a pretty straightforward risk/reward system, but the game still lacked any sort of threat. After a brainstorming session, the four developers felt that having a shark in play that could eat the fish made sense, and Bob Whitehead provided some graphical techniques he’d come up with for Boxing to create it. In all the visual fidelity and artistry on display in Fishing Derby rivals anything Atari had sold up to that point.

The game itself is a competition where two anglers are racing to see who can land 99 pounds of fish first. Fish closer to the surface are lighter and thus worth fewer points, but quicker to reel in. Fish deeper in take longer to bring up but are heavier, much as Crane’s risk/reward scenario planned. The shark is a real element of randomness – it will erratically speed up, slow down and change direction, meaning that the only way to really be sure you’ll land your catch is to steer as wide of it as you can. This is tricky though, as once you hook a fish, it’ll start being reeled in. You can speed up how quickly you reel your line back by holding down the button, but you can’t halt the process. Additionally, the fish is fighting the entire time and will drag your line left and right, which can inadvertently get it eaten by the shark.

David Crane has never been much for game variations, preferring to instead make a comprehensive game by itself, and as such Fishing Derby doesn’t really have many to choose from. Outside of basic one or two player options, the only other tweak comes from the difficulty switches. These adjust how readily fish will get hooked – on the A setting, the line needs to be set right where their mouths are. On B, it just needs to be near the front of their face to make the catch. This is a nice little option to allow veterans and newcomers alike to compete on the same basic level. The computer opponent is also no slouch, regularly going for the deepest fish available, though challenging it can get old fairly quickly. Fortunately, Fishing Derby is also a fantastic two player game, even 45+ years after its debut. On a platform known for its twitch action games today, this is a leisurely experience much as fishing itself tends to be.

So how was Fishing Derby received? In December 1980’s Video magazine edition, Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz reviewed all four of Activision’s initial games. On Fishing Derby, they remark that it’s an imaginative, colorful and fun all-ages game with better animation than a Saturday morning cartoon (which, if you’ve seen cartoons from 1980, isn’t a high bar) and a subtle degree of skill. The two also gave it an award at the end of the year for best audio/visuals in a video game, writing that its lavish graphics and smooth animation made this charming design “even more delightful.” Creative Computing’s roundup of VCS software in September 1981 covered it, where the magazine said it was not only a cute game, but that it was the favorite of all the girls and women in their review crew. These descriptions are interesting – at the time these reviews were published titles such as Pac-Man or Donkey Kong were just starting to reach western shores, and for a game that predates either of them, it’s especially rare to hear it described as cute or cartoony. And soon enough, that would be a popular aesthetic itself.

Additionally Fishing Derby, alongside Activision’s other games, would lead to a number of newspaper and magazine profiles about Crane and his fellow developers and the work they do, routinely noting how successful the company had been since starting out. I don’t have sales figures for most Activision games on hand, but a January 1984 Hi-Res magazine article about David Crane says that at the time a dozen Activision games had sold half a million copies. Given how common copies of the game are today, it seems plausible that this was one of them.

And Fishing Derby is a truly unique experience. The other three debut Activision titles are more or less renditions of existing games (even aping some Atari arcade projects in some cases), but Fishing Derby really comes out of the blue. There are practically no other fishing games on any home platform before the Famicom came out several years later in Japan, save for the incredibly obscure Fishin’ Hole written in BASIC for the Professional Arcade and published as a code listing in the Arcadian newsletter in May 1983. In that game you are simply raising or lowering your pole’s position in the water in between fish movements and hoping that their movements will coincide with where your hook is at. And even later fishing games were different experiences built off of what Japanese developers were doing – I’ve found no indication that Activision’s VCS games ever found their way into Japanese markets in the 1980s, so in a sense Fishing Derby not only started the fishing video game genre, it plays unlike anything thematically similar.

Activision would go on to become one of the most prolific third party publishers on the VCS, with 44 releases on the platform throughout the 1980s. The company’s success would lead to other Atari software developers abandoning the company to join with or form their own third party companies, which would lead to something of a brain drain at Atari itself. These pressures did bring on changes to how Atari handled its royalty structure, but all the major first party publishers continued to obfuscate the identities of the developers behind the games. The influx of third parties ate into Atari’s market share, and wound up leading to a software glut within a few years – frequently, albeit largely erroneously, blamed for the console market collapsing. But in 1980, with Space Invaders moving hundreds of thousands of consoles and cartridges and these new, colorful games on store shelves for those newly purchased VCS units, things are looking bright.

Activision itself has endured corporate shakeups, buyouts, and a horrifyingly gigantic merger with Microsoft, and while the company isn’t exactly the same entity it was back in 1980, it nevertheless has continued to publish games right up to the current day – essentially making it one of the oldest entities in the video game space to have been developing or publishing games that entire time. And that history started here, with a pair of anglers and a sea full of fish.

Sources:

David Crane, correspondence with the author, August 11-17, 2017

Larry Kaplan, interview with Scott Stilphen, 2006

Larry Kaplan, correspondence with the author, August-December 2017

A New Era Begins: Activision Exploits Atari’s Success, Video, December 1980

The 1981 Arcade Awards: The Best of a Great Year, Video, March 1981

They Create Worlds Volume 1, Alex Smith, 2021

New Games for the Atari Video Computer System, Creative Computing, September 1981

Fishin’ Hole, Arcadian, May 6 1983

Activision: More Games for the Atari, Electronic Games, Winter 1981

Meet David Crane: Video Games Guru, Hi-Res, January 1984

Activision to market video game/computer programs in spring, Merchandising, March 1980

Atari cites Activision in damage suit, claims trademark infringement, Merchandising, June 1980

Activision introduces four game cartridges, Merchandising, June 1980

Videogames: The Sky’s the Limit, Indianapolis Star, June 20 1982

First Video Game Publisher, Weekly Television Digest, April 28 1980

Atari vs. Activision, Weekly Television Digest, May 19 1980

Atari Game Suits, Weekly Television Digest, Dec. 7 1981

The People’s History of Computing in the United States, Dr. Joy Lisi Rankin, 2018

Release date sources:

Fishing Derby (August 1980): Weekly Television Digest, April 28 1980; New York Daily News, August 22 1980; Winnipeg Free Press, November 22 1980; Asbury Park Press, October 9 1980; Merchandising, June 1980

Fishin’ Hole (May 1983): Arcadian, May 6 1983