The vast majority of the early VCS games covered so far were games that the developers were personally interested in putting together. Whether these were ports of popular arcade games, conversions of tabletop timewasters, or novel concepts, marketing had largely stayed out of the way on what games came along and focused on selling them. But there were exceptions, even at this stage, of which Brain Games is one.

The crux of the marketing department’s request involves the VCS’s mix of controllers. You’ve got the two major ones that were packed in with the console itself from the get go: the joystick and the paddle controllers. The vast majority of the games on the platform use the joystick, which is surprisingly flexible for having one button. A smaller number use the paddle controller, which is much more limited in the types of games that it excels at; developer Larry Kaplan noted that marketing specifically requested that the programmers create games that use the paddles to ensure that users were still getting use out of them, which is why he put together Street Racer for the VCS’s 1977 lineup. The VCS also hosted two other controller types though: The driving controller, used in the system’s heyday with only Indy 500; and the keyboard controller.

The keyboard controller is more reminiscent of the keypads on the RCA Studio II or the APF MP1000 than any other type of control scheme on the VCS. It’s little more than an input device with 12 buttons, though since it supplants other controller types in whatever port it’s in, the keypads end up being useful only for very specific games. According to the book Atari: Business is Fun, the keypad controllers were actually a by-product of work being done by the VCS hardware design team, which was looking for ways to enhance the console after its launch. These various enhancements would ultimately come together in Atari’s 8-bit computer line in 1979, but the keypad was a holdover for these original plans, designed for a BASIC cartridge and logic-based games.

All told, ten cartridges would use the VCS keypad controller – or its later aesthetic variants, the children’s controller and the video touch pad – and three of those debuted with the keypads in October 1978. Two of these controller launch titles, Codebreaker and Hunt and Score, functionally bring some rather early computer game concepts to this comparatively inexpensive home game system. The third title, Brain Games, takes a slightly different approach, centered instead around an obscure Atari arcade game, alongside a music creation mode and some memory and mental agility selections.

Developer Larry Kaplan has no strong memories of creating Brain Games. He recalls at the marketing department told the programmers that they were putting out these keypad controllers, and that the company wanted games to go with them. At the time, he, David Crane, Bob Whitehead, and Alan Miller largely worked together in their own lab, and when a game was complete they “threw it over the wall” to sales and marketing. As a result, he didn’t have any other keyboard-centric developers to talk with. Instead, the ideas for that various gametypes in Brain Games were things he had to come up with on his own, supplemented by familiar puzzle games found in magazines and on computer systems, as well as an obscure Atari arcade game concept that was about to get its second wind. Kaplan said that he had to rush to finish the game by Christmas, which he doesn’t consider being particularly good.

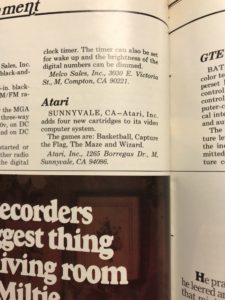

Atari first announced the game was coming in May under the working title “Wizard” alongside announcements for what would become Basketball, Flag Capture and Slot Racers; that announcement ended up appearing in the June 1978 issue of Merchandising. That information was already a bit outdated, though – by the June CES show Wizard had already been renamed to Brain Games when it was shown alongside six other cartridges.

Atari first announced the game was coming in May under the working title “Wizard” alongside announcements for what would become Basketball, Flag Capture and Slot Racers; that announcement ended up appearing in the June 1978 issue of Merchandising. That information was already a bit outdated, though – by the June CES show Wizard had already been renamed to Brain Games when it was shown alongside six other cartridges.

Brain Games, the title Kaplan’s collection was eventually sold under, is headlined by an official home conversion of Atari’s 1974 arcade game Touch Me. This game featured four buttons that would light up and produce sound effects; the player’s goal is to keep track of the sequence order and follow it. Each time it’s successfully completed, another button press is added to the sequence. If this sounds familiar, it’s because this was the exact same concept Ralph Baer would use for his successful 1978 toy Simon. Baer saw Touch Me at a 1976 Music Operators of America trade show and thought that it had a good play loop but was visually and aurally terrible. Howard Morrison, who Baer worked with through toy and game design group Marvin Glass & Associates, agreed, but they both thought it was worth looking into a handheld version of the game. Working with software guru Lenny Cope of Sanders Associates, they were able to program and build out a prototype unit in 1977, which was then successfully pitched to Milton Bradley, hit stores for Christmas 1978, and became a massive hit for years to come. Atari started selling its own handheld version of Touch Me in 1979, which makes Kaplan’s video game rendition the company’s first attempt to revive it for a new audience.

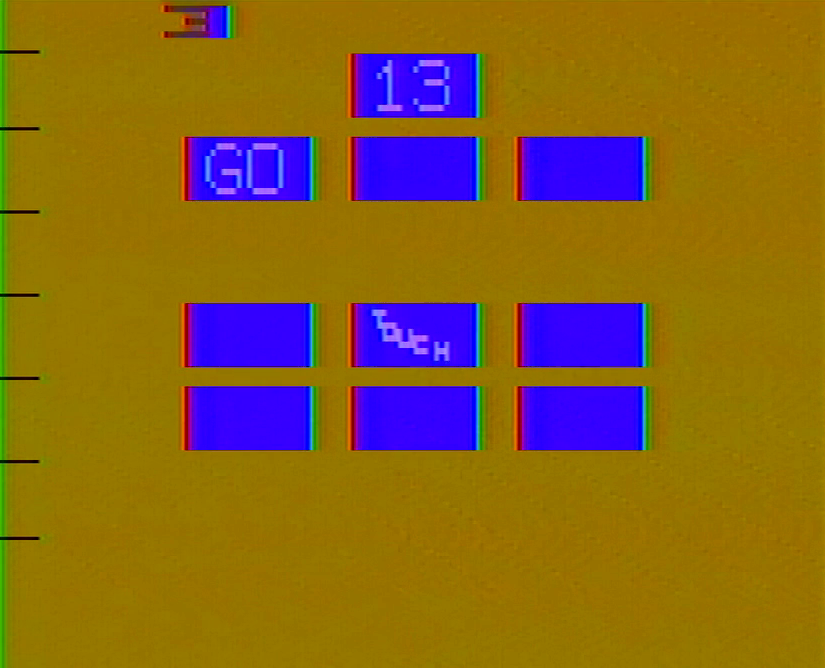

If you’ve ever played Simon, you know what to expect from the VCS version of Touch Me. The game will introduce a tone, requiring you to match it by hitting the corresponding button – either using six buttons or nine, depending on the game type. Each round will add a new tone to the sequence, maxing out at 32. If you complete that 32nd sequence or mess up four times, the game ends. You can adjust the challenge further with the difficulty switches – turning it to “a” will only give you a new tone, requiring the player to remember all the older ones.

Brain Games also has a similar gametype to Touch Me called Count Me, which essentially reverses the visual information – instead of matching tones to the buttons on screen, the game will instead show a number with the sound effect, and the player has to push that corresponding button as they go through the sequence. It essentially plays the same, so if you’re someone who likes Touch Me, you’ll probably enjoy Count Me as well.

Next on the cartridge is Match Me, a memory game. The VCS will briefly display a series of pictures, top to bottom, while matching it with an irritating sound effect as an attempt to distract the player. Once they vanish, the player has 20 seconds to arrange them properly, getting points for each correct answer and bonus points for speed. After five sets of objects, the game ends. The two Match Me gametypes only differ on how long you get to look at the original order before they disappear – either four seconds or one and a half. Difficulty switches simply adjust the bonus scoring to be either half the remaining timer or have it be one-to-one. It’s a neat little distraction for a couple minutes but there’s not much in way of longevity here.

Next on the cartridge is Match Me, a memory game. The VCS will briefly display a series of pictures, top to bottom, while matching it with an irritating sound effect as an attempt to distract the player. Once they vanish, the player has 20 seconds to arrange them properly, getting points for each correct answer and bonus points for speed. After five sets of objects, the game ends. The two Match Me gametypes only differ on how long you get to look at the original order before they disappear – either four seconds or one and a half. Difficulty switches simply adjust the bonus scoring to be either half the remaining timer or have it be one-to-one. It’s a neat little distraction for a couple minutes but there’s not much in way of longevity here.

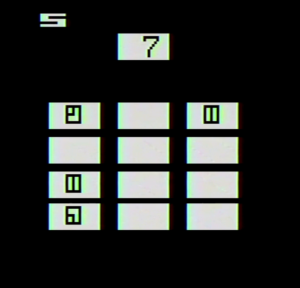

This brings us to Find Me, the next game on the cartridge. This game is also a memory test, but this time the focus is on subtlety. The player is shown a column of four images. Three of these are identical, but one of them has a minor difference – generally a pixel that has been shuffled around. It’s on the player to identify and select that image using the keypad, where each row of buttons corresponds to one of the images in the column. Depending on the gametype selected, either one or two players has either 20 seconds or five seconds to find which image is not like the others. The pressure is surprisingly real in the five-second gametypes, which can lead to errors and just entirely missing which one is different. Like Match Me, the difficulty switches adjust how many bonus points you get from the timer.

Add Me seems confusing at first, but is actually pretty simple. The game will show players a series of numbers, at which point you simply have to add up the value of all the digits and type in the correct answer using the keypad. With two players it’s a battle of basic math skills and the shame of adding up the numbers wrong; with a single player it loses a lot of the tension. Gametypes will adjust whether the game gives you four digits and 20 seconds to add them, or five digits and 5 seconds. Much like the previous two games, the difficulty switches adjust your point value from the timer.

Add Me seems confusing at first, but is actually pretty simple. The game will show players a series of numbers, at which point you simply have to add up the value of all the digits and type in the correct answer using the keypad. With two players it’s a battle of basic math skills and the shame of adding up the numbers wrong; with a single player it loses a lot of the tension. Gametypes will adjust whether the game gives you four digits and 20 seconds to add them, or five digits and 5 seconds. Much like the previous two games, the difficulty switches adjust your point value from the timer.

The final game on this cartridge is Play Me, which is less a game and more of a free range sound program. Each of the keypad controllers takes over one of the TIA chip’s two sound channels, with each button producing a different tone. The idea here is that you could use them to make music, and the instruction manual even includes a few sample songs using one or both controllers. To my knowledge, this might be the first tool designed for a gaming machine to produce homemade, chiptune music, though the limitations of the VCS’s audio capabilities and the inability to play anything back keeps this program from really shining.

Needless to say, Kaplan slapped together as many ideas for games as he could think of that would use the keypad controllers with this collection, but it’s not a particularly exciting release. Touch Me is the standout title here, and that’s really because of the Simon connection; the other gametypes are usually over in a matter of a couple minutes, though considering how easily any of them could overstay their welcome that’s probably for the best. If you’re into renditions of early puzzle games, this cartridge could provide a few minutes of entertainment.

Kaplan wasn’t the only person to hit on some of these game ideas, as they would appear on several other platforms. Touch Me, for example, showed up on the Magnavox Odyssey2 cartridge Math-A-Magic/Echo as the titular Echo game. This utilizes the system’s built in keyboard, allowing players to simply press the key to match the tone. And unsurprisingly, the RCA Studio II with its built-in keypads has a counterpart to Add Me built into the console itself called Addition. It plays almost exactly the same; add up the numbers before your opponent and get some points. Both of these renditions benefit from not needing specialized controllers to play.

At the time, Brain Games seemed to be looked at as a title to test one’s mental acuity, much as Nintendo’s Brain Age would do some 26 odd years later. The title is mentioned in the Chicago Tribune’s breakdown of video game consoles published March 14, 1979, where author Roger Verhulst said it emphasized concentration and mental agility, unlike more action-oriented titles. Steve Goldstein of the New York Daily News referred to it as one of the company’s educational games in his January 21st piece about setting up the ideal “Sports fan dream room,” which includes a VCS for downtime entertainment.

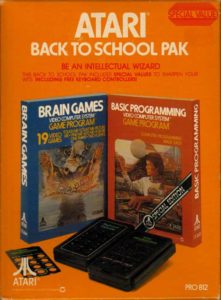

In 1982, Brain Games would get a second wind of sorts, being paired with later release BASIC Programming as the “Back to School” pack. On the whole, I’m not entirely sure how useful Brain Games would be for education, but someone in Atari’s marketing department clearly saw an opportunity, if nothing else, to try and move those games and excess keyboard controllers. Under the Atari Corporation years, Brain Games continued to be sold, albeit in fairly small quantities; the company moved about 5,900 in 1987, but scarcely more than a few hundred from 1986 through 1990 beyond that.

In 1982, Brain Games would get a second wind of sorts, being paired with later release BASIC Programming as the “Back to School” pack. On the whole, I’m not entirely sure how useful Brain Games would be for education, but someone in Atari’s marketing department clearly saw an opportunity, if nothing else, to try and move those games and excess keyboard controllers. Under the Atari Corporation years, Brain Games continued to be sold, albeit in fairly small quantities; the company moved about 5,900 in 1987, but scarcely more than a few hundred from 1986 through 1990 beyond that.

Though really, even those sales are impressive for a fairly mediocre package of games using a largely overlooked specialty controller. While you could do worse than to play Brain Games, the keyboard controllers never seemed to entirely catch on. While a home conversion of Touch Me is nice, this is likely the least of all the games that use these specialized input devices.

Sources:

Larry Kaplan, correspondence with the author, 2017

Atari: Business is Fun, Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, 2012

Videogames: In the Beginning, Ralph Baer, 2005

Merchandising, June 1978, January 1979

Weekly Television Digest, June 12 1978

Chicago Tribune, March 14 1979

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

Atari History Timelines, Michael Current