Rounding out the blockbuster year of 1980, Bridge is perhaps the most niche release to come out of Activision on the VCS. In fact, it’s arguably the most niche game on the platform. This is a single-player conversion of the team card game of the same name – a card game, it should be noted, that has appeared on home video game consoles approximately one time that I’m aware of, and that’s right here.

Bridge, nowadays generally short for contract bridge, is known as a trick-taking game, wherein players lay down cards trying to win each round for their team. Trick-taking games seemingly originated in China and became popular in Europe in the early 1400s. Bridge itself is something of a variant of whist, a card game that was popular in England in the 1700s and 1800s before largely being supplanted by bridge in the 1890s. The modern form of contract bridge stems from a man named Harold Stirling Vanderbilt in 1925, who came up with a few improvements to the game he’d thought up to make bidding a bit more interesting – coming up with the idea of a “contract.” Within a year his version of the game had spread across the United States, becoming a hugely popular social pastime since all it took was four people and a deck of cards to play. Bridge even became the star of an ABC television show, Championship Bridge with Charles Goren, who was a renowned bridge player who had written instruction books and kept up regular columns for newspapers and Sports Illustrated about the game. Bridge remained a popular game up into the late 1960s, when interest began to wane among younger players. While bridge tournaments and sessions still draw decent crowds, most players are, at minimum, in their 50s. What happened is a bit unclear – it’s possible other areas of entertainment, such as television or video games, drew attention away from bridge. Poker has really supplanted it as the card game of choice for groups of people, and without the same degree of strategy and mind games as bridge, is a much easier game to get decent at.

I’ve had no experience with this game before playing this cartridge for this project, so apologies if I don’t quite get the rules exact, but here’s my understanding of them. Bridge involves two teams of two people split up by direction, with one team being north and south and the other being east and west. After the cards are dealt, players “bid” on a contract – essentially determining how many rounds or tricks need to be won by a team, and which suit, if any, will be the “trump” suit that will outrank all others. Once a contract is agreed on by everyone else passing, the game begins. One player will play a card, with play continuing clockwise until all four hands have been played; normally speaking players must play a card with whatever suit the initial player put down, with the highest value card winning. That is unless they have no more cards of that suit in their hand; in this case they can play a card from another suit, and it that card is from the “trump” suit then they will beat out pretty much anything but a higher value card from the trump lineup. Play continues until there are no more cards left in anyone’s hand, and scores are tallied based on whether or not a team achieved the contract (with adjustments based on if they ended up over or under the number of winning rounds they needed). Then the cards are dealt again and everything starts over again until a set number of points are achieved.

While computerized bridge options existed by the end of the 1970s, such as the standalone Bridge Challenger or the Apple II Bridge Challenger game, these were expensive options. Between the VCS’s growing popularity and relatively low cost compared to an Apple II or dedicated bridge machine, producing a version for Atari’s machine was a sensible alternative. Additionally, even though by the time Activision’s game had come out, bridge was already fading as a pastime among the primary audience for the VCS – predominantly kids and teenagers – there was still being a pretty sizable number of people interested in the game broadly. And since these kids typically lived in family units, it made some sense for a bridge game to exist targeting older crowds, such as parents.

Bridge was the first game Larry Kaplan wrote under the Activision label. Kaplan had initially planned to join Activision with the other three founding programmers in 1979, but after having a falling out over the business plan, abandoned that effort to work for Commodore on a speech synthesis project. After quickly seeing the writing on the wall for that effort, he rejoined his Activision comrades around January 1980, albeit with a 50% cut in stock options for coming in late. Kaplan said that he’d played bridge for about 10 years by that point and really enjoyed the game, playing in bridge duplicate tournaments with Jack Verson, a friend of his. Kaplan decided to make a video game version of it to help “train” people, or at the least keep them entertained when they couldn’t find three other players. Verson, a game developer in his own right, became a helper on the project. Kaplan said Verson assisted with the AI, bidding and playing, adding that while he and Verson had programmed together at work they’d never actually co-wrote a game. Kaplan also believes David Crane assisted him with the graphics on the Bridge cart, something that Crane didn’t seem to have much recollection of, though Crane did note that his mother, an avid bridge player, loved Kaplan’s cartridge. In all, Bridge took Kaplan around six months, and ended up needing a 4-kilobyte ROM chip to store the program – which he considered a source of some shame, given that Activision’s previous releases all fit on 2k cartridges. The initial release had a glitch where the computer would make an illegal bid sometimes and crash the game, requiring them to change the ROMs for future runs of the cartridge and stockpile a few in case of consumer complaints.

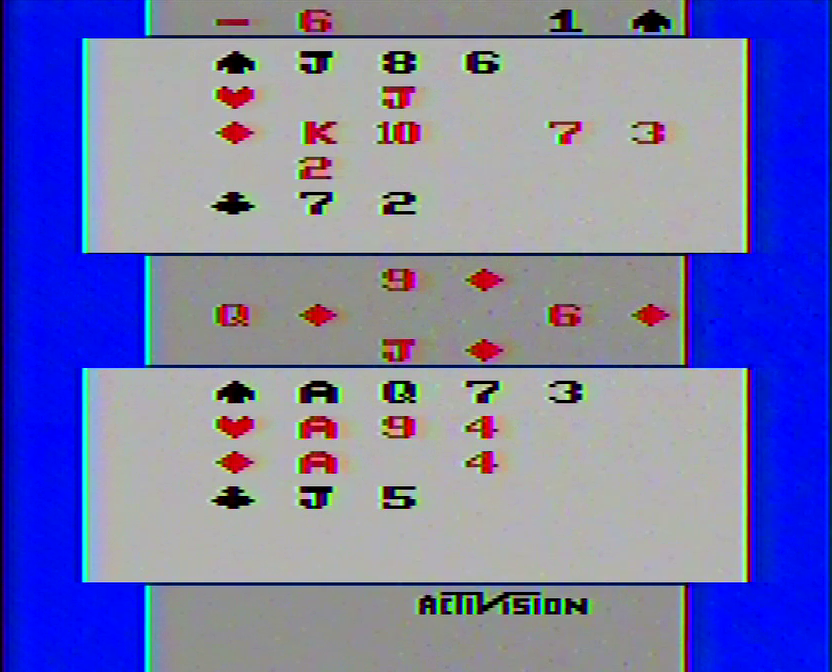

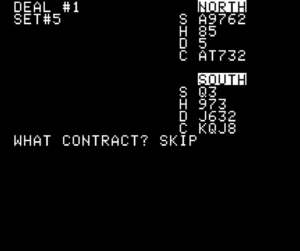

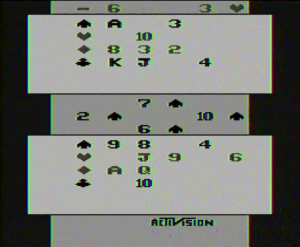

The cartridge itself has two main modes. The first three game types allow for bidding between the player and your computer partner, with the opposing team members, east and west, passing on their turns. The computer will bid based on the cards in its hand, which normally speaking the player cannot see unless they flip the left difficulty switch to A. These three game types change what the minimum partnership point counts are – essentially a system of evaluating the strength of players’ hands; game type 1 has 21 or more, then 25 and 29 for the following variations. Game types 4 through 7 skip the bidding process and simply allow the player to select the contract, with minimum point counts ranging from 21 through 29 again.

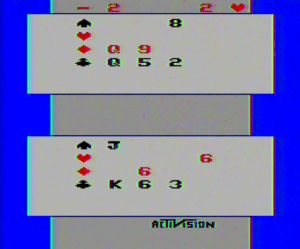

Once the bidding is done and the contract established, your team member will lay down their hand for you to see, with the player controlling which cards both north and south put down. Whoever wins a round will be the one to select the first card to put down for the next round until all cards are played. The number of tricks to go to reach the contract is displayed in the upper left, with red indicating that the player’s team is under the contract and black indicating they are over. The upper right shows the contract chosen. Normally speaking the east and west hands are not shown on screen; flipping the right difficulty switch will let you see what cards those players held at the end of the match, with E indicating the east player. This isn’t terribly helpful information given that the match is over at that point, but it can provide a player with some insight into what led to the computer’s decision-making on what cards to play. If the right switch hasn’t been flipped, players can replay the same hand by pushing the fire button, or push it when the P is flashing on screen for a new hand to be dealt. If the right switch is on A, then you’ve got to hit the reset button on the console to get a new hand dealt.

While the rules for bridge are a little convoluted for newcomers, the VCS game is fairly easy to grasp with a little help from the internet. Bridge may be a niche product, it’s a solidly made game. Rounds go by quickly once you know what you’re doing, and while the manual assumes you already know the rules – since why else would you buy a bridge cartridge? – it seems like a pretty helpful learning tool. Computers have always struggled to play a strong game of bridge even up to today, but the VCS does all right at it. Bridge isn’t the ubiquitous phenomenon it was when the VCS cart came out, but this is a good way for a newcomer to get their feet wet and learn a favored game of earlier generations.

Bridge was featured in the ANALOG magazine’s VCS update in the May/June 1981 issue, and despite lamenting that Kaplan’s game did not allow the opposing team to make its own contract bids, it nevertheless would play intelligently each round and was one of the better adult games on the VCS. The game also had a short writeup in the Muncie Star that September, where the author called it one of the finest practice tools for the game around. The game was even reviewed in 1983, when Calgary Herald writer Bill Musselwhite reviewed the game favorably, stating that despite its limitations it is a fun game that can help a player improve. Positive praise from bridge fans aside, however, Bridge is one of the harder Activision titles to come across today, which suggests it was just as niche a seller as one would expect. As it turns out, being targeted at adults when the primary audience for home games at the time was much younger didn’t appear to make Bridge a mass-market phenomenon. According to a consumer column in the Wilkes-Barr Times Leader from 1984, Bridge was discontinued in late 1983 and was not widely stocked in the first place, but did better for the company on the east coast than anywhere else. Activision at the time did appear to still have some copies of the bugfixed version available in case of returns… or in this case, for a bridge fan still looking for it.

As for Kaplan, once Bridge was completed he set about making assembler tools for the Intellivision platform so that Activision’s team could begin making games for that console as well. In 1981 he would come back to game development on the VCS with his final game on the platform, the well-regarded Kaboom!. While Bridge is pretty much the exact opposite of that frenetic release, there really isn’t anything like it on the VCS library… or any of its competitors, for that matter. Bridge essentially stands alone on the home console space as the sole attempt to translate the card game ever, as far as I can tell. Perhaps it’s due to bridge players’ preference for in-person sessions or online play, or maybe the primary audience for home console gaming has just never come around to bridge. In any case, this is a perfectly playable attempt at the game.

Bridge wraps up the VCS list of releases for 1980, and the home gaming market is in a radically different place than it was at the end of 1979. On the strength of Space Invaders, the VCS has exploded in popularity, in turn forcing Atari to rapidly scale up its operations. While it had the strongest sales out of all its competitors in the 1970s for a number of reasons, thanks to Space Invaders the VCS platform would dominate the home market in North America. For reference, by the end of 1979, Atari had sold a total of approximately 600,000 VCS units, totaling 1.3 million in homes including its 1977 and 78 sales, and the company controlled 80% of the cartridge market. Space Invaders for the VCS bolstered the VCS platform dramatically, with Atari selling about 1 million more VCS units in 1980 along with around 1.2 million copies of the game itself, ending the year with 67% of the console market and 79% of the cartridge market by dollar value.

As a comparison, the VCS’s closest active competitor in the North American market at the start of 1980 was Magnavox’s Odyssey2, which had sold about 225,000 units between 1978 and 79. The Odyssey2 itself saw its first major ad campaign in 1980, but without the name brand of Space Invaders under its umbrella Magnavox only sold about 160,000 units that year – not bad, but a far cry from what Atari was doing. But 1980 also saw the wide release of the Mattel Intellivision. While Mattel’s flagship console was test marketed in small quantities in November and December 1979 – with a release under the Mattel branding in Fresno, California, and under the Sylvania brand in Baltimore, Philadelphia and Washington DC – its test marketing would expand in March 1980 to include more parts of the country before achieving a nationwide release in August. Mattel took different marketing approaches than Atari with the Intellivision. Initially the company would emphasize the upcoming keyboard component that could expand the machine into a full computer system. When it was clear from market feedback tests that the keyboard component wasn’t really all that interesting to consumers, Mattel shifted gears to making direct comparisons of its games to Atari’s – notably the sports games, which were generally more complex simulators than what you could find on competing platforms. A huge ad campaign centering on the relatively famous sportswriter George Plimpton was massively successful, with Mattel selling through its 190,000 unit stock of Intellivisions and 1 million cartridges – giving it about 20 percent of the console market and 11% of the cartridge market. The Intellivision would become the closest thing to a rival platform to the VCS in its heyday, and though its install base and library would be dwarfed by Atari’s machine it would end up being the only one of these competing platforms to remain active on the market through the entire 1980s.

As for the minor players in the console market, after spending 1979 liquidating Channel F stockpiles, Zircon announced four new games for the platform in an August press release that could be mail ordered by Channel F owners. While these were practically all games that were finished at Fairchild before the company fell apart, they were all also pretty decent titles that seemed to convince Zircon it was worth commissioning some additional releases that would drop the following Christmas. And after struggling to sell its Professional Arcade following problems with FCC approval, quality control and sticker shock, Bally looked to offload its consumer division in 1980 – first to Fidelity Electronics early in the year, and after that fell through, to an Ohio-based outfit eventually called Astrocade that August. At this point Bally Arcade sales were pretty paltry – an estimated 28,000 units were sold in 1978 with around 80,000 produced. Astrocade had its own internal political struggles and questionable decision-making by its sales department that kept the Bally Professional Arcade a bit player in the console space, with only an estimated 128,000 units sold by late 1983. Among the BPA enthusiasts, however, 1980 was a good year – the system had a new owner that was committed to supporting it, Perkins Engineering – the name of an enthusiast hardware outfit ran by father and son Clyde and John Perkins – released the first RAM expansion for the console, called the Blue RAM, and a continued array of homemade software made its way to fans. Finally, APF did not put out anything new for its MP1000 console, focusing instead on the Imagination Machine computer expansion that had come out in late 1979; neither it nor the MP1000 saw much impact on their respective markets.

Arcades, meanwhile, were in the midst of their so-called “golden age,” where arcade games would make some serious money and could be found pretty much anywhere. Atari published seminal works such as Centipede, Battlezone and Missile Command, all of which would eventually find their way to the VCS. Other companies such as Stern and Cinematronics published hits of their own, like Berzerk and Star Castle, with the former getting an excellent VCS conversion and the latter inspiring the original Atari game Yars’ Revenge. But the eventual monster hit was Pac-Man, which came out midyear in Japan and made it to American shores in November courtesy of Bally/Midway. Pac-Man didn’t start out as the cultural phenomenon it’d become, beginning its commercial life as a moderate success that would snowball in popularity until by mid-1981 it was a fad all its own. Atari would eventually snap up the home rights and make a mint putting Pac-Man on practically every viable commercial platform under the sun, both on the console side and on home computers.

While the home computer market was ostensibly distinct from home consoles and arcades, there were early moves here that would eventually impact the console side as well – though no one could possibly have recognized it at this point. In North America it was really dominated by the Apple II+ on the high end, and the newly introduced Commodore VIC-20 and TRS-80 Color Computer on the low end, and Atari attempting to fulfill both sides with its 400 and 800 computers. The first three were essentially successors from the so-called 1977 trinity of the original Apple II, the TRS-80 and the Commodore PET, though admittedly the II+ was effectively an Apple II with some of the optional upgrades already included. The VIC-20 would be the first computer to be sold in normal toy retailers like video games were, and not just specialty shops, and alongside its relatively affordable $300 price tag it was an attractive option for consumers looking for a first home computer platform. While notable games from other companies like Zork and Mystery House shipped in 1980, for Atari that was the year when the critically acclaimed Star Raiders really gained notoriety as one of the best games of its era. Star Raiders combined the strategy of the popular and ubiquitous Star Trek computer game with Star Wars-style cockpit action against alien ships. Even though Atari’s computers never dominated the market like the VCS would, Star Raiders would be an incredibly influential work and was undoubtedly the killer app for the company’s computer line the same way Space Invaders would be for the VCS.

Ultimately we are in the early period of Atari’s dominance in the American gaming space, and for the VCS 1981 features a sizable contingent of games considered the cream of the crop on the console. With new third-party publishers and new games from Activision and Atari, VCS developers would continue to push the boundaries of what people thought possible on the platform in its fifth year on the market.

Sources:

Larry Kaplan, interview with the author, 2017

Larry Kaplan, interview with Scott Stilphen, 2006

Video Computer System Update, ANALOG, May/June 1981

TV Games Update, Rick Teverbaugh, The Muncie Star, Sept. 5 1981

Computer Show Will Have Displays, Seminars, Bill Musselwhite, Calgary Herald, June 7 1983

Leader Action, Wilkes-Barr Times Leader, Oct. 12 1984

Grand Slam, Score!, 1983

No PET Peeves, Peter Fee, Creative Computing, January 1981

They Create Worlds Vol. 1, Alex Smith, 2019

Intellivision: How a Videogame System Battled Atari and Almost Bankrupted Barbie, Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman, 2024

Mattel Hiked Prices, Weekly Television Digest, Oct. 15 1979

Video Game, Weekly Television Digest, August 11 1980

Warner Video Boom, Weekly Television Digest, April 13 1981

Bally/Fidelity, Arcadian, March 24, 1980

Bally Sold, Weekly Television Digest, Sept. 29 1980

Astrovision Takeover, Arcadian, Nov. 6 1980

Blue RAM ad, Arcadian, June 23 1980

Astrocade: One More Time, Mark Brownstein, Video Games, June 1983

Pac-Man: Birth of an Icon, Arjan Terpstra and Tim Lapetino, 2021

Release Date Sources:

Bridge (December 1980): Activision press release, September 1980; St. Joseph Herald Palladium, December 24 1980; Merchandising, November 1980; Battle Creek Inquirer, December 25 1980