The 1970s were a time of rapid growth and change in the nascent video game industry. Over the course of the decade, arcade video games were commercially introduced, grew in complexity, and shifted from black-and-white to color. But the video game industry as we know it started in the home, and there was a great deal of interest in bringing those arcade experiences back to the rumpus room. Much like the earliest arcade games, early home consoles were dedicated machines capable of only playing whatever the circuitry had built in. There was no real programming involved because there weren’t really microprocessors available to run these games; as such game design was in large part a function of hardware design. Although Magnavox’s Odyssey system functionally was the home market for the first few years – featuring changeable cards that, under the hood, were little more than circuitry that told the hardware to use specific rules for whatever game – around 1975 the market was flooded with dedicated consoles that largely worked to recreate the popular arcade game Pong. Such a market was always going at risk of becoming a fad the same way that CB radios or digital watches were, and electronics giants like Fairchild and RCA were in a race with arcade game developers such as Atari and Bally to change that paradigm and hit the storefronts with consoles capable of interchangeable, new games with a sturdier shelf life.

Atari’s effort, the Video Computer System, had its first proof-of-concept prototype design completed on paper in December 1975, by engineers Steve Mayer and Ron Milner of Cyan Engineering, which was a subsidiary of Atari. Mayer and Milner had been discussing how to follow up Atari’s Home Pong dedicated console that summer when Mayer suggested moving away from dedicated consoles, which required designing from the ground up new circuits and hardware for each new game, to building a base unit with different ROM chips that could be plugged into it to run games instead. The idea of porting the popular arcade game Tank – which was produced by another Atari subsidiary, Kee Games and published in November 1974 – was in the front of the engineers’ minds as a natural follow up to Pong. The initial prototype design included the idea of running what would become Combat on the eventual system, and used the arcade machine’s dual-stick control setup to run a basic version of Tank as a proof-of-concept. A second pair of hardware designers named Jay Miner and Joe Decuir were charged with building out that prototype design and turning it into a commercial product, with one basic edict: That the VCS should be able to run home versions of Tank and Pong, as well as home versions of other popular arcade titles such as Jet Fighter and Gran Trak 10.

Decuir has said in interviews that the VCS was built with the practical limitations of what technology was available in 1975 and ’76 while also being cost-effective for a consumer product. Their final design featured a stripped down 6502 CPU, 128 bytes of RAM, and a custom graphics chip called Stella. Some of the design compromises ended up being strengths; notably, the system lacked the ability to build a display all at once as a frame buffer, as Fairchild’s Channel F and RCA’s Studio II did. This left programmers to use precious CPU cycles to time out the screen line-by-line, before calculating inputs, collisions and other actions during the overscan period, effectively racing the television’s electron beam down the screen and back around from the top. This challenging quirk ended up being key to the system’s longevity – with programmers firmly in control of screen display line-by-line, tricks like starfields, sunsets and the “venetian blinds” kept the system looking and playing better than its contemporaries into the early 1980s. It also allowed the display to move much more smoothly than its early competitors, before the affordable technology was there to improve frame buffer displays.

Decuir has said in interviews that the VCS was built with the practical limitations of what technology was available in 1975 and ’76 while also being cost-effective for a consumer product. Their final design featured a stripped down 6502 CPU, 128 bytes of RAM, and a custom graphics chip called Stella. Some of the design compromises ended up being strengths; notably, the system lacked the ability to build a display all at once as a frame buffer, as Fairchild’s Channel F and RCA’s Studio II did. This left programmers to use precious CPU cycles to time out the screen line-by-line, before calculating inputs, collisions and other actions during the overscan period, effectively racing the television’s electron beam down the screen and back around from the top. This challenging quirk ended up being key to the system’s longevity – with programmers firmly in control of screen display line-by-line, tricks like starfields, sunsets and the “venetian blinds” kept the system looking and playing better than its contemporaries into the early 1980s. It also allowed the display to move much more smoothly than its early competitors, before the affordable technology was there to improve frame buffer displays.

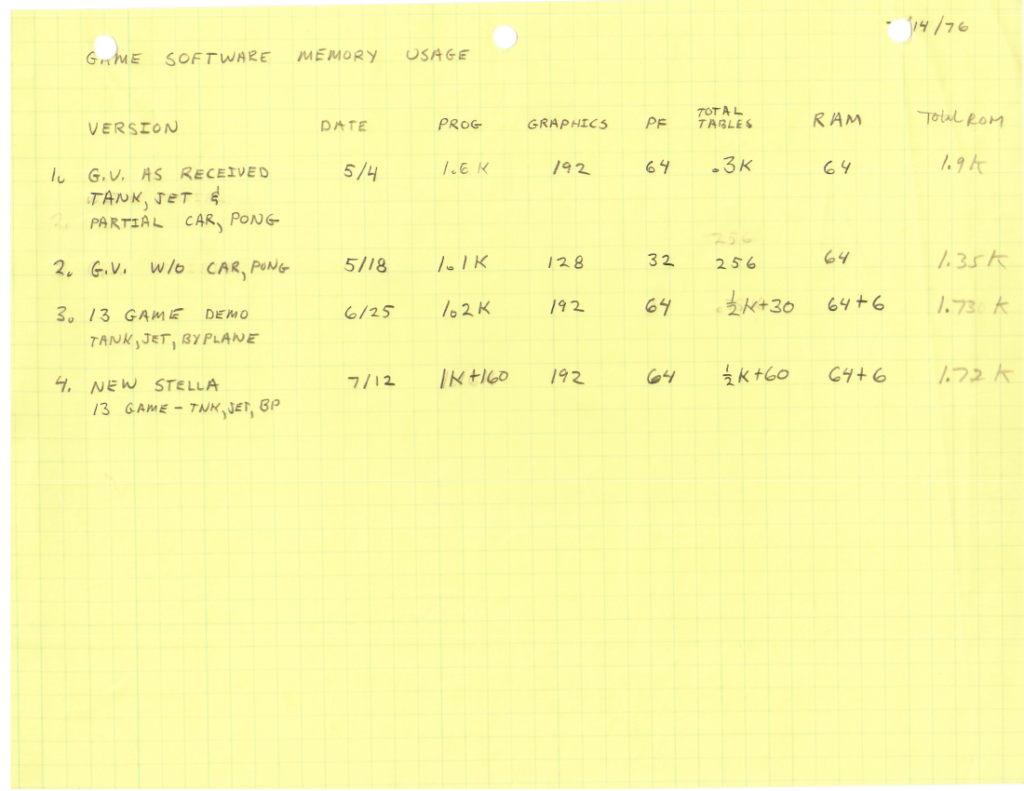

But in 1976 and ’77, the system design was being finalized alongside that of its Tank conversion. Calling himself little more than an “implementer” based on Mayer and Milner’s concepts, Decuir got the basic display engine running for Tank on the VCS before passing the project along to Larry Wagner, Atari’s head of game development. Wagner says that the game continued to evolve on the fly as the hardware continued to be worked on, with at least four major variations of the game existing depending on what decisions were made. Interestingly, the first version from May 4, 1976 included a car racing game and a version of Pong; both of these would be dropped in the next revision, and by July Wagner had a handle on what variations would appear on the cartridge.

Multiple variations were a selling point that became the standard for VCS games in its early years. Essentially each cart would have either several games united by a theme or a number of tweaked versions of a single game that allow for more replayability and challenge. In the case of Combat, The Tank game featured remixes of the basic premise that included invisible tanks and more complex mazes, to the mode Wagner is most proud of, “Tank Pong,” which allowed shots to bounce around the field. Wagner explained that at the time he was commuting to Los Gatos from Berkeley for work, which was at the time a mellow, relatively low traffic experience that gave him time to think. During one of those drives Wagner hit on the idea and started thinking about how to implement it on the VCS prototype. This in turn also led to an additional variation, a billiards mode, where players could only score a point after a ricochet shot.

Combat isn’t just a home conversion of Tank. Wagner included a port of Atari’s Jet Fighter arcade game, which had been released in October 1975; Wagner didn’t remember how this specifically came about, but believes that he, Decuir and Miner all were going through Atari’s coin-op library looking for game ideas, saw Jet Fighter and collectively decided to have Wagner implement it. Jet Fighter in turn had its own variations that Wagner came up with, adding in obscuring clouds or replacing the aircraft with biplanes. No input on the game console was wasted. The difficulty switches were used to determine how far shots would go, essentially allowing a better player to handicap themselves against a weaker one. After approximately two minutes and 16 seconds, a contest between two players would end, and the game would return to its color-cycling attract mode. The Select switch cycled through the different gametypes, while Reset started the selected game – a much simpler arrangement to get a game going than the Channel F or Studio II’s byzantine sequences of button presses. And cognizant that most people still had black-and-white televisions in their homes in 1977, Atari made sure the color switch on the console would flip the game to a black-and-white TV-friendly mode, where all the colors became grayscale. Wagner notes the only hardware feature that went unused in Combat was the “ball” sprite. In retrospect he said it could have been used to make a “killer field” or something along those lines, but the idea had not occurred to him at the time.

Combat isn’t just a home conversion of Tank. Wagner included a port of Atari’s Jet Fighter arcade game, which had been released in October 1975; Wagner didn’t remember how this specifically came about, but believes that he, Decuir and Miner all were going through Atari’s coin-op library looking for game ideas, saw Jet Fighter and collectively decided to have Wagner implement it. Jet Fighter in turn had its own variations that Wagner came up with, adding in obscuring clouds or replacing the aircraft with biplanes. No input on the game console was wasted. The difficulty switches were used to determine how far shots would go, essentially allowing a better player to handicap themselves against a weaker one. After approximately two minutes and 16 seconds, a contest between two players would end, and the game would return to its color-cycling attract mode. The Select switch cycled through the different gametypes, while Reset started the selected game – a much simpler arrangement to get a game going than the Channel F or Studio II’s byzantine sequences of button presses. And cognizant that most people still had black-and-white televisions in their homes in 1977, Atari made sure the color switch on the console would flip the game to a black-and-white TV-friendly mode, where all the colors became grayscale. Wagner notes the only hardware feature that went unused in Combat was the “ball” sprite. In retrospect he said it could have been used to make a “killer field” or something along those lines, but the idea had not occurred to him at the time.

The finished product, released as Combat, ended up as the pack-in title with the VCS when it started to hit retail in 1977. The system’s early competitors had built-in games, a reasonable move since the home market was predominantly dedicated consoles. Though this had been considered for the VCS during development, Atari ultimately decided to pack in a cartridge containing a pair of its arcade titles. This made the system’s design abundantly clear. This was a machine built around modular games, completely unlike the vast majority of systems already on the market. That Atari included a cartridge also suggests that they were aware that people expected to be able to play their new game system out of the box.

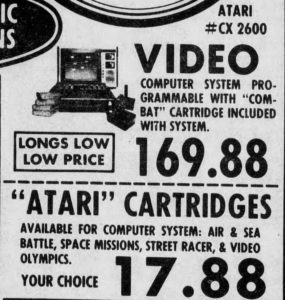

Of course, since no one was keeping track of release dates at that point in time, the only clues to when the VCS and Combat launched are based on early advertisements, which started running regionally in California that August and begin appearing across the US in newspapers that September from retailers like Long’s Drug Stores, Sears, Macy’s and PayLess Super Drug Stores. Combat was also sold separately, as the giant retailer Sears packed in a different game with their Tele-Games branded version of the VCS. The system and Combat immediately existed as technological steps above the Fairchild Channel F and the RCA Studio II, with smooth action, greater color depth and more natural sound effects. The Channel F’s own Tank clone, Desert Fox, was written by Vilas Munshi and hit stores alongside the Channel F in November 1976, is an example of the hardware differences. While Munshi’s game includes the arcade version’s land mines, the movement of the tanks and their shots are much jerkier, and it lacks the gameplay options and richochet shots Combat brought to the fore. The Studio II never saw a home Tank conversion, but Atari’s future competitors from Magnavox and Bally – the Odyssey2 and Professional Arcade, respectively – received their own unlicensed home ports at their platform launches the following year. Tank may have been a few years old by that point, but it was still a popular enough game to be worth bringing out.

Even the game’s lack of a single player option played to Atari’s strengths. At the time of the VCS’s launch, the vast majority of home games were multiplayer; this made sense, given that cartridge games were working with limited space while programmers continued to figure out these new platforms. But beyond being a routine design decision in the 1970s, it also meant that new people would have to be introduced to these games so that the owner – or their family members – would have someone else to play the games with. According to DeCuir, Atari sold in excess of 250,000 units in the first year, and it seems likely that word-of-mouth played a role in that early success.

Combat ended up becoming synonymous with the Atari VCS, sticking around as a pack-in until 1982, and continuing to be sold separately. Internal Atari Corp sales figures from 1986-1990 available online show that Combat still had market interest even at that time, with 21,054 units sold in those years, proving that even a game so long in the tooth and so primitive compared to what the VCS would host in the coming years still had people willing to pay for new copies. Even today virtually everyone who owns the VCS has at least one copy sitting around somewhere, and unsurprisingly, the successive owners of the Atari catalog have continued to make it available, either on dedicated Atari Flashback consoles or included in game collections on modern platforms. Atari even announced a sequel, Combat II, in 1982, but the game went unfinished and officially unreleased until the prototype was included in 2005’s Atari Flashback 2 console. Combat may not feature some of the fancy visual effects or gameplay complexities of later VCS releases, but it continues to stand as one of the system’s finest multiplayer experiences. Not bad for the first game ever designed for the platform.

Combat ended up becoming synonymous with the Atari VCS, sticking around as a pack-in until 1982, and continuing to be sold separately. Internal Atari Corp sales figures from 1986-1990 available online show that Combat still had market interest even at that time, with 21,054 units sold in those years, proving that even a game so long in the tooth and so primitive compared to what the VCS would host in the coming years still had people willing to pay for new copies. Even today virtually everyone who owns the VCS has at least one copy sitting around somewhere, and unsurprisingly, the successive owners of the Atari catalog have continued to make it available, either on dedicated Atari Flashback consoles or included in game collections on modern platforms. Atari even announced a sequel, Combat II, in 1982, but the game went unfinished and officially unreleased until the prototype was included in 2005’s Atari Flashback 2 console. Combat may not feature some of the fancy visual effects or gameplay complexities of later VCS releases, but it continues to stand as one of the system’s finest multiplayer experiences. Not bad for the first game ever designed for the platform.

Sources:

Joe Decuir, interview with the author, September 3 2017

Larry Wagner, interview with the author, August 25 2018

Joe Decuir interview with Scott Stilphen, Atari Compendium, 2005

Joe Decuir presentation, Portland Retro Gaming Expo, 2015

Atari: Business is Fun, Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, 192-217, 2012

They Create Worlds: Volume 1, Alex Smith, 327-342, 2019

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, 2016 (unpublished manuscript)

Release Date Sources:

Combat, August 1977: The Sacramento Bee, August 1, 1977

Los Angeles Times,August 20, 1977

Miami Herald, August 29, 1977

Desert Fox, November 1976: Channel F Launch Brochure, November 1976

Panzer Attack (Bally Professional Arcade), January 1978?: Merchandising, June 1977 insert lists as planned launch game

Weekly Television Digest, December 26, 1977 says system coming out with 3 games + 3 more later in January

Bob Fabris letter to JS&A dated march 15 says 5 games in catalog

Baltimore Sun, November 5, 1978

Armored Encounter (Magnavox Odyssey2), September 1978: Creative Computing, September 1978

Weekly Television Digest, May 22 1978

Colorado Springs Gazette, November 28, 1978