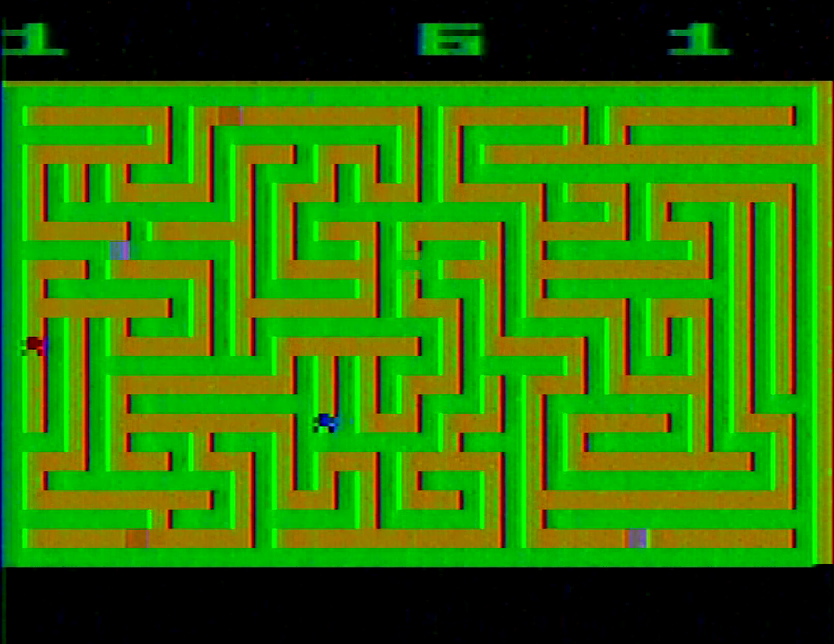

September 1980 saw a surprising amount of maze-related content published on the VCS. In addition to Carla Meninsky’s Dodge ‘Em, Atari also published Rick Maurer’s follow-up to the smash hit Space Invaders: Maze Craze, also known as Maze Mania under its Sears title. And unlike Dodge ‘Em or 1978’s Slot Racers, Maze Craze is less about doing things within the maze so much as it is about navigating the maze itself.

Maze games do have a bit of a computer gaming pedigree. Among the earliest game programs was MOUSE, known colloquially as Mouse in the Maze, a demo for the TX-0 computer by Douglas Ross and John Ward that was first publicized in January 1959. This program allowed users to design a maze with a light pen and set loose a computer-driven mouse to try and find cheese laid down throughout; if the mouse didn’t get cheese within a certain time period, it would lose energy and the game would end. Another version of the game swapped the cheese out with martinis, and had the mouse “stagger” its way through the maze as it got progressively drunker. MOUSE was, in turn, directly inspired by Claude Shannon’s 1952 Theseus Maze, a problem-solving electromechanical mouse that used relays to navigate a maze that the user designs, looking for the robot equivalent of cheese. But neither of these can really be considered a game in the modern sense; rather they are both AI experiments. Actual games built around mazes would not exist until the 1960s, when a maze program was developed at the RCA Sarnoff Labs for the 1967 25th anniversary of the lab’s founding.

Developed by Charles Wine and James Miller, Maze was designed to showcase some of the computer technology at the RCA Sarnoff Labs to attendees. In this case, it used a Tektronix 564 storage tube oscilloscope monitor, which could hold an image on screen for a few minutes, and a custom-built joystick and button box serving as a “teletype” for a DEC PDP-6 computer located at nearby Princeton University. The PDP-6 would then output the display to the storage tube. Under normal circumstances, this storage tube would be linked with a teletype for use in creating graphs and engineering designs, but for something interactive and easily grasped by laypeople, Wine and Miller’s supervisor, Bernard Lechner, suggested a game.The computer itself would randomly generate an 8×8 “chessboard sized maze,” Wine told me in an interview, and players used the joystick to navigate through it. A line would appear on screen indicating the direction a player had moved in each square, assuming they did not run into a wall. The screen didn’t instantly display the maze, either – in some settings, the walls only appeared as players moved through its corridors. Each time a player bumped into the wall, it would produce a “ding” sound, subtract a point, and draw in that section of the maze; with the storage tube, these walls would remain on the screen until the player cleared the maze and the computer generated a new one. Upon completing the maze, the entire maze would be drawn in so that players could see how roundabout a path they took to clear it. Other optional game types would flash the entire maze on screen upon running into a wall before starting the player back at the beginning, put the players against a timer, or only drew in the line tracing players’ path without ever displaying the walls.

There are a couple other known computer maze programs; the 1961 Minivac computer designed by Claude Shannon used mechanical relays, but still had a handful of games it could run, including The Electronic Maze, wherein one player designs a simple maze and challenges another to navigate it. Additionally, by 1972 the Dartmouth Time Sharing System had, among several other games, AMAZING. When ran, this program built a randomized maze of any dimensions specified by the user up to a 23×25 matrix, which would be guaranteed to have a single solution. Since the DTSS used teletypes, it’s likely that this created the maze on a piece of paper that the user could then tear off and solve at their leisure, but nevertheless, as a rudimentary computer-generated maze program goes this is a very early example.

The arcade space appears to have been a leading edge in this regard. In October 1973 Atari published Gotcha, a rudimentary maze game where one player scores points by touching the second player, while the second player earns points over time for simply not being caught. As recorded in the Atari: Business is Fun book, Atari engineer Al Alcorn indicated that he got the idea from defective Pong arcade boards. He said that a bad gate in the circuit that put up the scores on screen would cause the segments that make up those numbers to appear all over the display. Alcorn connected that defective portion to a motion circuit, causing segments to move around the screen, in essence creating an ever-changing dynamic maze. Steve Mayer of Cyan Engineering built this idea out into a functioning game, albeit one that he looked back on as “awful.” Two dots chasing each other around a shifting maze was certainly unusual in 1973, but Gotcha is perhaps better known today for having a salacious design in the early, prototype cabinets where the controls were shaped like breasts, a design choice credited to George Faraco that went unused in the production units. It is also also notable for its color graphics variant that came out at the same time; while most Gotcha machines were either straight black-and-white or used colored overlays on the screen to mimic a color display, a small number were produced with a daughterboard capable of adding color. This makes Color Gotcha one of the earliest arcade games to feature color graphics – even if the production run was incredibly small, estimated between 20 and 100 units.

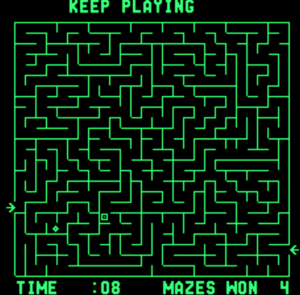

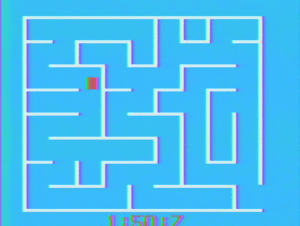

The next true leap in maze game technology came with the advent of the microprocessor, however. Dave Nutting Associates was a pioneer in the usage of microprocessors in arcade games, with their title Gun Fight being among the first game to use one instead of discrete circuits when it was published by Bally/Midway in 1975. According to interviews with developers Tom McHugh and Jamie Fenton, Jeff Frederiksen initially tested out their Intel 8080 design by having it randomly generate mazes. This test would be turned into a full game around November 1976 called The Amazing Maze, using Frederiksen’s existing maze generation code as its core and with additional work by Frederiksen and McHugh (and Fenton noting that she probably contributed a bit given the collaborative environment of Dave Nutting Associates). The Amazing Maze is a time-based game where two players work to navigate these randomly generated mazes and try to be the first one to escape through the opponent’s entryway. Escaping a maze netted a player a point, and whoever had the most points at the end of the time limit won. This was a huge step forward for the maze game genre, and was a clear influence on what would develop on home platforms in the coming years.

Before we get to those, however, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that Dungeons & Dragons was first published in 1974 and would grow in popularity through the rest of the decade. These early incarnations of the tabletop role-playing game were, functionally, maze games – the game was designed around the idea that players would venture into labyrinths, fight monsters, and earn treasures and acclaim in the process. While it’s unlikely that this had any influence on the console maze games, Dungeons & Dragons undoubtedly was a force in computer maze games like the PLATO program dnd, the Apple II game from 1978 Dragon Maze, where Gary Shannon tasked players with escaping a maze before a dragon attacked them; or early role-playing video games like Akalabeth, where players had to navigate a labyrinth… marking a parallel evolutionary track to that seen in coin-op machines. Even early text adventure computer games such as Colossal Cave Adventure and Zork were effectively their own type of maze programs.

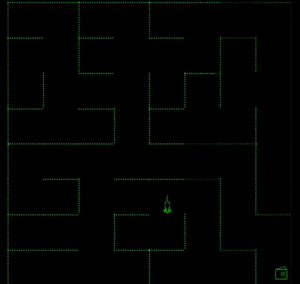

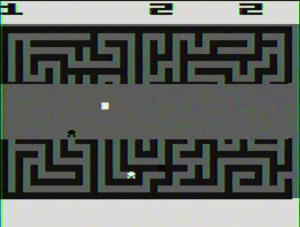

Back in the console realm, the late 1970s into the early 80s saw a slew of maze games, where players competed to get through a maze with a varying degree of obstacles in the way. The earliest of these was Maze, developed by Michael Glass and published by Fairchild for the Channel F in November 1977. Glass unfortunately passed away in 2003, and at the 2004 Classic Gaming Expo his former coworker (and Maze Craze developer) Rick Maurer said that he didn’t know where Glass drew his inspiration from for it. Yet it doesn’t take much of a leap to see how Maze owes a great deal of itself to Amazing Maze. Maze features randomly generated maps that players must maneuver through, though in this case both players start at the same entrance. Glass included a few variations to keep things interesting: there’s a jailbreak mode where the walls contain hidden passages and a “blind-man’s bluff” mode where the path through is invisible and players can shroud their tracks as they maneuver through. Adding to these modes are options to play “cat and mouse” where a computer-controlled cat comes into the maze from the exit and tries to eat the two players, a paranoia version where the game cannot end until one player has been eaten by the cat, and a final mode with no cat or exit – just a maze to wander around until you get bored. When one mouse completes the maze, it will change color to reflect theirs, indicating who won the game. All in all it’s a pretty feature-complete package, and for someone who liked The Amazing Maze in the arcade, this is a good approximation.

About a year after Fairchild’s game was released, Bally released a home conversion of The Amazing Maze on the Professional Arcade. Developed by Bill Jahnke, this home Amazing Maze is essentially identical in gameplay to the arcade original, with randomly generated mazes and players starting on opposite ends. It lacks all the variations of the Channel F game, but it does have a bit more audio/visual flair, and lets you set the victory score to whatever point total you want. Fenton said that home conversions of Bally-Midway games generally entailed passing along the source code to the arcade original to the home developer, which likely explains why Amazing Maze for the Professional Arcade hews so closely to its bigger cousin. The Bally Arcade also featured a BASIC game called Memory Maze wherein the screen will flash a maze for ten seconds before turning it invisible; the player starts with nine points per maze but will lose one point for running into a wall and three for bringing up the maze again to help navigate – providing a bit of a risk reward arrangement if you don’t have a great memory or don’t want to cheat with a smartphone. In some ways Memory Maze seems to draw from Wine and Miller’s RCA project, but given that author Steve Walters appears to have lived in Michigan, it’s unclear if he ever saw that game at RCA’s New Jersey labs or if this is just a case of convergent evolution. Memory Maze appears to have been sold on cassette through the Arcadian newsletter starting in December 1980 – only a short time after today’s game reached stores.

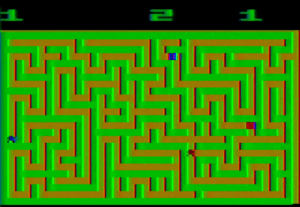

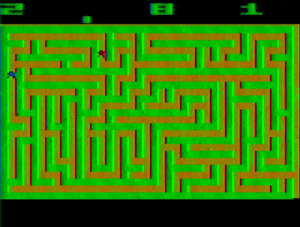

And this brings us to Atari’s Maze Craze. The game itself is directly inspired by Glass’s Channel F Maze, according to comments by Maurer. In his interview for the Stella at 20 documentary, Maurer said he’d been working on Space Invaders for about four or five months before deciding to shelve it – both due to a lack of interest from Atari staff, and from not being able to figure out how to get rid of intense flickering on the invaders. Maurer then started working on his own version of Maze, in turn setting that aside to finish Space Invaders once Atari management became interested in releasing it. After that he returned to his maze game to finish it as well. Maurer indicated he deliberately chose not to include a score in Maze Craze, which sets it apart from Bally’s games but is in keeping with how the Channel F game is designed. The manual does shift the premise from Glass’s game: instead of cats and mice, the objects on screen are now cops and robbers. The text assumes you’re a police officer and for the purposes of this video we’ll stick with the booklet’s explanations, but honestly it doesn’t make a difference: let your little stick person represent what you want.

Much like games that use a lot of computational cycles like Video Chess or Video Checkers, the VCS will throw up a screen of random color flashes while it designs its random mazes and ensures they’re capable of being finished. This isn’t actually that unusual, as both versions of Amazing Maze will also fill the screen with garbage and sounds while it generates a maze. The Channel F title simply displays part of the maze wall before generating the interior, by contrast, but given its different architecture from the VCS hardware (where a lot of memory and computer cycles need to be actively devoted to drawing the screen) Maurer’s solution is probably the best one to ensure the maze loads as quickly as possible.

Maurer noted that he loved adding variations to games going back to his Fairchild days, and this is on full display with Maze Craze. Besides the standard “go through the maze” mode, there are eight major variations in different combinations that result in 16 major game modes. There are capture settings, where the player characters – considered cops in the manual – must catch three robbers before they can win the game. There’s “robber” settings, where two, three or five computer-controlled opponents try to catch the human players to knock them out of the game, and they must be avoided. There are “wound” games where if touched by a robber the player’s character will continue along their path for a few seconds; a terror mode where you cannot win until your opponent has been knocked out by a robber; a “blockade” mode where you can put up fake walls to trick your opponent, and invisible maze games. These invisible mazes are in turn broken down by three more variants: one where the maze flashes on screen periodically, one where players can “peek” at the full maze by pushing the button, and one where players have scouts that randomly move throughout the maze and show the paths around them. Finally, each and every one of these 16 gametypes allow you to select game speed and the degree of visibility between four degrees each, leaving you with a whopping total of 256 individual variations on this game to appreciate. The difficulty switches will also adjust player speed to either be as fast as robbers or faster than they are, adding an additional wrinkle. You may recognize some of these gametype descriptions from the Channel F game, but there is certainly a lot more to work with here if you’re into the genre. The robber modes and the “terror” gametype are all lifted straight from the Channel F Maze, as is the idea of leaving fake walls behind you in blockade games.

Maze Craze has game types that work for one player, though it defaults to having a second player always on screen. Played by oneself, Maze Craze is a decent enough experience – the computer-controlled robbers can be tricky to evade in the 2, 3 or 5 robbers and the terror gametypes, and hard to catch in the capture games. The maze options with limited visibility can be tricky to maneuver through: in auto peek game types you only have a few moments to see the maze every so often, during which the computer is continuing to move through the level, and player peek modes can be similarly exasperating given that they have a recharge time between uses. The scout gametype is an interesting take, however: the scouts can be activated by pushing the button on the controller and only travel a short distance, but will effectively show you every passageway near your present location. The visibility options can be sorely missed in the gametype with no variations at all if you have low visibility turned on.

With two players, Maze Craze gets a bit more interesting. Players for the most part are unable to impact one another besides leaving fake walls behind in blockade mode, but there is a heightened sense of urgency in trying to clear a maze before your opponent, or attempt to avoid an enemy robber before they stop you in your tracks. The low visibility modes are again a bit frustrating, but do help level the playing field if one player is much better than the other at solving mazes. This all said, maneuvering through the maze can prove tricky on the speedier gametypes, as Maze Craze is particularly unforgiving about overshooting an intersection. While this is a little bothersome in single player games, it can make or break an attempt to finish two-player games before your partner.

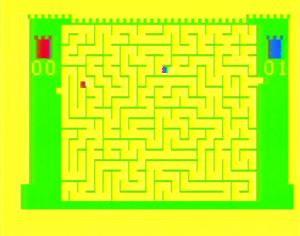

There is one more maze game to touch on here, exclusive to the Videopac G7000 – the European Odyssey2 – and published in 1981 called Labyrinth. While there is a normal “work your way through the maze” game type, this version also brings back the moving maze shape from Gotcha. In those modes, the walls will constantly shift around, meaning you can be stuck waiting for a passage to open up to reach the goal. Also, you can set the goal to move too, in case you wanted to be a little more annoyed. It’s a pretty decent take on a maze game, but after seeing what competing platforms had put together it does seem like a thin experience with much simpler mazes.

Maze Craze did receive accolades in Creative Computing’s September 1981 roundup of VCS software, wherein author David Ahl remarked it received high marks from their review team. While he found the low visibility mazes more frustrating than fun, particularly the game type with scouts, he wrote that everyone in their team seemed to have at least one favorite variation. In Video Action‘s roundup of Atari’s fall software published in March 1981, Howard Kaye wrote that it was challenging and enjoyable, adding that both it and fellow release Dodge ‘Em were loads of fun but dull in appearance. While as of this writing there is no information about how the game did on the market in the early 80s, Atari Corp did ship 3,016 copies between 1986 and 1988 – fairly paltry numbers, but arguably about as well as you’d expect from a game whose genre had really left it behind.

Maze Craze came out at a time when the maze game genre was really evolving in a few new ways that rendered it more of a curiosity by 1986. The novelty of mazes being randomly generated by a computer was no longer really enough to sell a game like it did a decade earlier in 1976. Instead, you started seeing maze games where the levels were predetermined and the player had to achieve specific goals within the labyrinth. For example, some games like Wizard of Wor required players to move through the game space eliminating monsters. Others, like Rally-X, Head-On, or Pac-Man, required players to dodge foes while collecting specific items to reach the next stage. And on computers, the maze genre was moving into first-person territory with D&D inspired games like Wizardry, and eventually this would lead to first-person shooters like Faceball 2000 and Doom… and first-person games on the VCS like Escape from the Mindmaster. While Maze Craze does what it sets out to do admirably well, the game really released at a time when what it does was rapidly being overtaken by innovations elsewhere. Still, that’s enough for Maze Craze to have a following who do appreciate the game – it’s arguably the best game of its type produced at the time, and remains eminently playable today.

This also likely represents the last VCS game for 1980 published by Atari. Maze Craze, Dodge ‘Em and Video Checkers were all announced alongside a fourth game, Championship Soccer, but it is unclear from newspaper advertising if the latter actually reached store shelves at the same time, or, more likely, if it was delayed by a few months into 1981, likely to secure an endorsement by soccer player Pele.

As for Rick Maurer, he moved over to the coin-op division of Atari to work on the Asteroids sequel Space Duel before leaving the game industry entirely; another developer, Owen Rubin wound up completing Space Duel. After a few appearances at the Classic Gaming Expo in the mid-2000s, Maurer has effectively vanished, and it’s unclear if he’s simply done talking about his video game work or if he has unfortunately passed away. His VCS legacy is very much secured though, with two very good games – one a platform-defining work and the other the pinnacle of its genre –under his belt.

Sources:

Stella at 20 materials, Glenn Saunders, 1997

Reminiscing with Richard Maurer, James Hague, dadgum.com, Jan. 5 1999

The Fairchild Channel F Panel, Classic Gaming Expo 2004

Interview: Tom McHugh, Ethan Johnson, thehistoryofhowweplay, April 3 2018

Jamie Fenton, interview with the author, Dec. 2 2020

Charles Wine, interview with the author, Aug. 27 2021

Jeff Frederiksen, correspondence with Paul Thacker, Sept. 29 2011

Bernard Lechner’s deposition, Magnavox v Chicago Dynamic, 1976, Hagley Museum and Library, M&A 1191

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

New Games for the Atari Video Computer System, David Ahl, Creative Computing, September 1981

Prima Facie, Howard Kaye, Video Action, March 1981

Ads, Arcadian, Dec. 5 1980

New Games Join Home Video Craze, Shreveport Journal, Nov. 19 1980

Atari Adds Four Games, Announces Major Promotion, Leisure Time Electronics, Fall 1980

One, Two, Three, Four, I Declare a Space War, They Create Worlds, Alex Smith, 2020

Ch…Ch…Changes, Atari Inc: Business is Fun, Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, 2012

The Origin of Spacewar!, J.M. Graetz, Creative Computing, August 1981

Mighty Mouse, Daniel Klein, MIT Technology Review, Dec. 19 2018

Theseus, MIT Museum

Fixing Color Gotcha, Ed Fries, Edfries.wordpress.com, May 25, 2016

History of Softape – Part 2, Keith Smith, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com, Dec. 27 2014

Oral History of Steven Mayer, Computer History Museum, June 24, 2024

The Tangled Cultural Roots of Dungeons & Dragons, Jon Michaud, New Yorker, Nov. 2 2015

Machines at Play, Dungeons and Dreamers, Brad King, 2003

Interview with the Creators of dnd, Carey Martell, RPGFanatic.com, April 26 2012

Minivac 601 Books V and VI, Book VI: MINIVAC Games, 1961

A User’s Guide to the DTSS Program Library, 1972

Release date sources:

Maze Craze (September 1980): Lansing State Journal, September 24 1980; Daily Herald Suburban Chicago, October 22 1980; Shreveport Journal, November 19 1980

Amazing Maze (Bally, January 1979): Arcadian, January 13 1979

Maze (Channel F, November 1977): Channel F News Vol. 1, Issue 1 October 1977; Weekly Television Digest, October 24 1977; Chicago Tribune, October 12 1977; Naples Daily News, September 21 1977; Spokesman Review, December 3 1978

Memory Maze (Bally BASIC, December 1980): Arcadian, Dec. 5 1980

A Labyrinth Game/Supermind (Philips, 1981): manual copyright date