Most of the Atari VCS games we’ve looked at so far are ones where you know what you’re getting into just from the title. A game named Indy 500 is probably about racing. Space War is most likely going to have you fighting in outer space. Blackjack is going to involve playing cards, and so forth. But then you get to Slot Racers, and you’re probably going to be kind of baffled. What the heck is going on here, you might ask? After all, slot racing in real life is little more than model cars you insert into an electrically connected track and drive around a predetermined route. This game has player vehicles driving around a maze shooting at each other. If you have the Sears version of the game, which was released under the title Maze, you might have a better idea of what you’re getting into here. But the reason Slot Racers seems so far removed from the source material is because that wasn’t the premise in the first place.

But before we get into that, we have to step back a moment and recognize that Slot Racers is the first Atari VCS game developed by Warren Robinett. Best known for his seminal 1980 VCS game Adventure, Robinett was part of the second hiring wave of Atari home video game programmers, coming on board in November 1977 – shortly after other notable Atari developers like David Crane and Jim Huether joined the company. Robinett wrote about his experiences at Atari and developing Slot Racers in his book (unpublished as of this writing), and graciously provided me with a copy of the manuscript to help describe the development of his three VCS titles. He also explained to me that he felt that the best way to figure out how to program a game for the VCS within its limitations is to just start writing a complete one, and while driving to work one day he had an idea in his head for a game he called “Traffic.” In it, two cars would be driving around a city maze firing rockets at each other in a severe case of road rage.

But before we get into that, we have to step back a moment and recognize that Slot Racers is the first Atari VCS game developed by Warren Robinett. Best known for his seminal 1980 VCS game Adventure, Robinett was part of the second hiring wave of Atari home video game programmers, coming on board in November 1977 – shortly after other notable Atari developers like David Crane and Jim Huether joined the company. Robinett wrote about his experiences at Atari and developing Slot Racers in his book (unpublished as of this writing), and graciously provided me with a copy of the manuscript to help describe the development of his three VCS titles. He also explained to me that he felt that the best way to figure out how to program a game for the VCS within its limitations is to just start writing a complete one, and while driving to work one day he had an idea in his head for a game he called “Traffic.” In it, two cars would be driving around a city maze firing rockets at each other in a severe case of road rage.

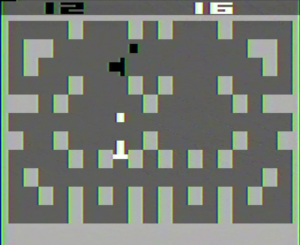

With that concept in mind, Robinett looked to Combat for inspiration on how the game could control. He liked the idea of the player having to orient themselves to the direction of their vehicle, with left and right on the joystick turning them left and right from whatever direction they were already facing; on the flip side, he didn’t like how the game reacted when a tank drove into a wall. For his Traffic game, Robinett decided he wanted to ensure that the vehicles could smoothly move around corners, which would ultimately set it apart from the Tank game on Combat.

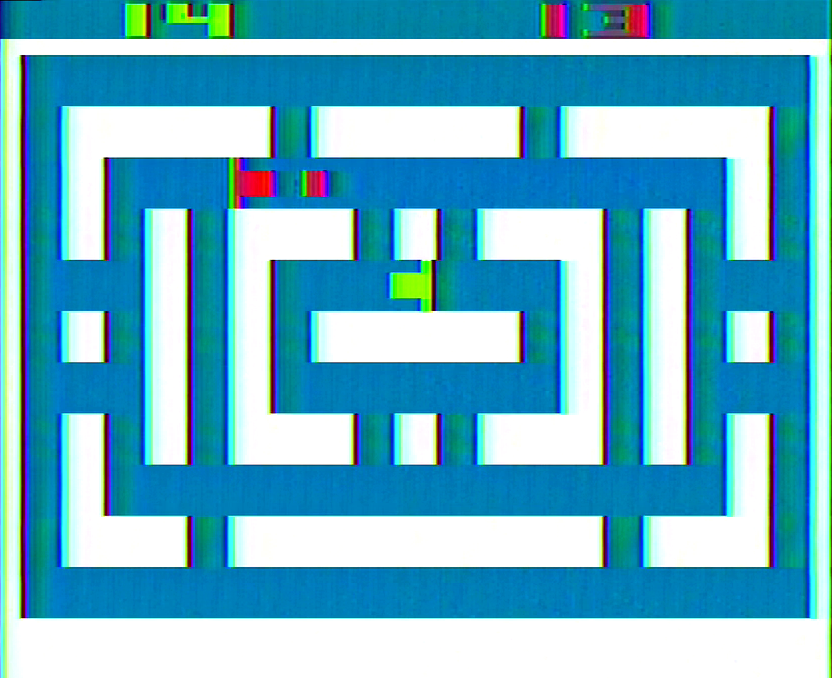

From there the design was iterative – he came up with different mazes, adjusted the speed and momentum of the vehicles, and ultimately produced a pretty unique game for the platform. Maze games up to this point were largely based around navigating your way through the labyrinth, such as in Midway’s Amazing Maze arcade game, or for chasing around the other player, as in Atari’s Gotcha. Robinett’s premise placed the maze less as the focus of the game and more of a playfield to navigate through in service to a broader goal. This already puts it in the same field as later maze games such as Sega’s Head On or Namco’s Pac-Man, a remarkable feat for an original first game for a new developer in 1978, even if Robinett himself felt the final product came out somewhat average.

From there the design was iterative – he came up with different mazes, adjusted the speed and momentum of the vehicles, and ultimately produced a pretty unique game for the platform. Maze games up to this point were largely based around navigating your way through the labyrinth, such as in Midway’s Amazing Maze arcade game, or for chasing around the other player, as in Atari’s Gotcha. Robinett’s premise placed the maze less as the focus of the game and more of a playfield to navigate through in service to a broader goal. This already puts it in the same field as later maze games such as Sega’s Head On or Namco’s Pac-Man, a remarkable feat for an original first game for a new developer in 1978, even if Robinett himself felt the final product came out somewhat average.

Finally, for reasons unknown to Robinett, Atari’s marketing department changed the name from Traffic. Atari announced the game shortly before the June 1978 Consumer Electronics Show under the name “The Maze,” and appears to have dropped even that for the title Slot Racers, even though the company’s own marketing materials basically described the game as Robinett had envisioned it.

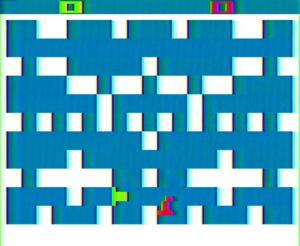

Much as Robinett planned, Slot Racers has two players driving cars around one of four mazes. Hit your opponent with a rocket, and you get a point, sending them flying in the process. The first player to get 25 points wins the game. You can turn the car left and right at intersections, and both speed up and slow down your car by pushing up or down on the joystick. The difficulty switches will either let you fire a new missile at any time – erasing the current one on screen – or will force you to wait for your missile to either hit your opponent or get picked up by the player before letting you fire again. In a twist, in all but two gametypes players can also control the missiles to some extent by pushing a direction while firing – holding left or right while firing a missile will cause it to go in that direction, while holding none will cause it to drift forward and turn at every corner it comes to.

In addition to changing the maze, higher numbered gametypes will also cause the cars to move faster. Gametypes 1 through 4 also speed the missiles up with each increasing number, while gametypes 5 through 7 give you cars that move faster than the missiles. Finally, gametypes 8 and 9 feature missiles that are unable to take corners, along with the choice between slower cars and fast ones.

Unfortunately, Robinett was unable to include one final gameplay item from his original premise within the 2k of cartridge ROM space available to him; he wanted police cars with blinking lights to also be cruising the maze, chasing the players. But even without that additional aspect, it’s a pretty decent little game – it might not be a VCS classic, but it’s worth putting on and playing a few rounds with some friends. Gametype 1 moves awfully slow and is really only good for getting the hang of how the game plays before moving on to the more complex mazes and faster speeds – these are where Slot Racers shines.

Contemporary press agreed with this assertion as well. In the June 1981 Arcade Alley column in Video Magazine, authors Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz note the title has nothing to do with the game but nevertheless consider it to be one of the most important of the “classic” maze games. They considered it to be quite a thrilling game requiring quick thinking and fast reflexes, and recognize that while it takes some practice to get the hang of steering, it’s well worth it.

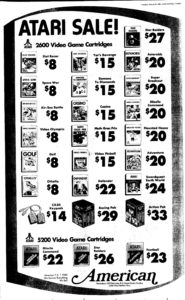

Robinett remembers turning in the final code for production in April after five months of development time. Advertisements for the game indicate that it started showing up in stores alongside the rest of Atari’s 1978 lineup around October. While Atari’s internal sales figures are fairly spotty at this point, it does not appear to have been one of the top sellers on the platform. Slot Racers would be paired with 1977’s Indy 500 in a “Racing Pak” bundle around June 1982, presumably as a way to move copies of the two aging games. Slot Racers did sell a small number of copies in the later days of the VCS’s life – in addition to appearing in some of the final Warner-era Atari catalogs in 1983, a whopping 48 copies were sold in 1987 by Atari Corp, with another 77 the following year. This doesn’t make it the rarest of the Atari Corp rereleases of earlier games, but it is certainly among them.

Late 80s sales aren’t really the legacy of Slot Racers though. It’s an early example of a well-done maze game years before Pac-Man made it a dominant genre, and a nifty two player game in its own right. But this was the first step on the road Robinett took towards developing Adventure, a game where he took the ideas of navigating a maze into new directions, and the wall interaction routines he created for this game found their way into his much better known follow up. While Slot Racers may be little more than a roadside motel on the way to that destination, at least it’s a pretty nice one.

Sources:

Making the Dragon, Warren Robinett, 2018, unpublished manuscript (and thanks to Warren for sharing it with me!)

Video Magazine, June 1981

Merchandising, June 1978

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

Atari History Timelines, Michael Current