Atari’s fourth and final game from July 1980 follows in the footsteps of games like Night Driver, Outlaw, Indy 500 and numerous others in being a home conversion of a 1970s arcade game that is much, much better known today by its VCS counterpart. And much like Outlaw before it, Circus Atari – or the much more direct Sears title, Circus – is an unlicensed version of another company’s original; in this case it’s Exidy’s 1977 arcade game simply named Circus.

Circus, and by extension Circus Atari, is a take on the brick-breaking formula established by Atari’s Breakout. Instead of bouncing a ball off a paddle into a wall of colored bricks, however, the player controls a see-saw operated by two clowns. At the start of each life, one of the clowns will bounce off a platform on the side onto the see-saw, sending their counterpart flying up into three rows of drifting balloons. Popping balloons earns points; clearing one of the two bottom rows will get the player bonus points, while clearing the uppermost will earn you points and a free life. It’s a clever game that is more interesting than Breakout, and serves as something of a counterpoint to that title co-designed by the father of the single player ball and paddle genre, Howell Ivy.

Ivy was a developer with the company Ramtek in the early 1970s, creating their arcade game Clean Sweep, which would later serve as the inspiration within Atari for Breakout. Ivy would eventually leave Ramtek to co-found Exidy with Pete Kauffman and Bob Newsome, where he would kick off the company’s arcade legacy with Destruction Derby and, more famously, Death Race, an arcade game with the premise of running over “gremlins” with your car. Ivy paved the way for Exidy to move into microprocessor-based arcade games with his next title, Car Polo, before reusing much of that hardware for the company’s next game. Ivy explained in an interview with Retro Gamer magazine that since developing new hardware was difficult, he liked to find ways to reuse as much of what they already had designed as possible. As such, much of the same hardware used in Car Polo would be reused again for this unique twist on Breakout, which was based on an idea by Kauffman.

In the case of Circus, Ivy and his codesigner, Edward Valleau, did more than just trade out the cars from Car Polo for balloons. Circus features flailing, hapless stick figures that represent your clowns – Ivy said it was a way to inject some personality into the game, and alongside the lighthearted premise of the game, to try to draw in more female players. While we don’t have demographic breakdowns of Circus’s player base, it was in any case a huge success for Exidy, with an estimated 7,000 units sold in 1978. Circus became one of the biggest hits that year, with the company’s facilities being filled up with Circus machines as their manufacturing worked on the necessary parts for the game. This situation led to Exidy licensing the game out to Bally-Midway, which released its own version as Clowns, and crucially to Taito for the Japanese release under the title Acrobat. Breakout was a massive success in Japan, and Acrobat did incredibly well for itself in that country, inadvertently sparking the video game music genre. The designers included a few little tunes in Circus that play when you start the game, when you lose, and when you pop the top row of balloons; Exidy in fact billed the game as the first arcade game that generated its own music without needing a tape player or some other specialized hardware. These and the game’s sound effects were noticed by the music industry veterans that contemporaneously formed Japanese supergroup Yellow Magic Orchestra: Ryuichi Sakamoto, Haruomi Hosono, and Yukihiro Takahashi. YMO would sample it and other early arcade games for their first, self-titled album in November 1978. Their track Computer Game “Theme from the Circus” opened the album, and alongside the second track Firecracker would be a successful single in Japan, the US and the UK. Computer Game would influence the hip hop and techno scenes outside of Japan, and Hosono would produce one of the first full-length albums specifically for game music in 1984, simply titled Video Game Music. YMO itself would form the record label GMO in 1985 to publish video game soundtracks into the mid 1990s. Suffice it to say, Circus casts an unexpectedly long shadow in some interesting corners of the video game space.

Unsurprisingly for such a big arcade hit, Circus would find its way home, both as a number of clones on computer hardware and clones to game consoles. Bally-Midway got there first on the Professional Arcade platform, releasing a version in 1978 that uses the Clowns branding of the company’s own arcade rendition of Circus. In a 1982 interview with Electronic Games, developer Bob Ogdon mentioned that this was not only his first game program that he’d ever written, it was among the first home games to use four kilobytes of memory space for the program. Speaking with Ogdon myself, he remarked that space was a concern for all their games at the time, and that the developers used to pay each other to look for ways to save space in the code. Electronic Games author Arnie Katz declared Ogdon’s home version was so good that it hadn’t really been surpassed in the years since. By all rights, dropping this home version of Clowns so shortly after the arcade release should have been quite a coup for Bally. Unfortunately for the company, the Professional Arcade suffered from production and quality assurance problems from its planned fall 1977 release all the way through its actual debut year in 1978. These issues, coupled with Bally’s minimal experience with the consumer electronics space in general, lost it all the potential momentum it could have had, and the machine would remain a bit player in the market essentially its entire shelf life. Nevertheless, this early home version has your flailing clowns popping well-rendered balloons alongside musical stingers, making it a solid take of a then very new game.

Atari’s own version was developed in part by Michael Lorenzen, who was also responsible for fellow July release Golf. In addition to my own interview with him, back in 2013 Lorenzen did talk with Ferg of the 2600 Game by Game podcast, who relayed to me some of Lorenzen’s development memories as well. Based on these discussions, Lorenzen said that Circus Atari was originally started by another developer entirely who couldn’t get the game to work. This developer then either left the company or was fired, and work was halted. Then, Lorenzen surmises, someone from marketing saw a screenshot of the game and put it in a Christmas catalog for retailers; upon learning it didn’t exist, Atari then brought back the original developer as a consultant to try and finish it, though by that point they had already gotten another job, so they only came in at night to work on the game. As soon as Lorenzen had finished work on Golf, he was tapped to surreptitiously help out on this Circus conversion. Funnily enough, he added that he had no experience with the original Exidy coin-op title prior to being asked to assist with this cartridge. The original developer – who Lorenzen declined to name – would save his code onto eight-inch floppy disks and lock them in a cabinet when he was done for the day. Lorenzen was given instructions to then take those floppies back out and continue to work on the game, making sure he put them back when he in turn was finished. The idea, he said, was for him to figure out the other person’s code well enough that Atari could end his consulting agreement and have Lorenzen take it over to completion; Lorenzen remarked that this would’ve been easier if he’d been able to just start from scratch rather than try to make sense of someone else’s code, but he was able to eventually figure out what the developer was trying to do and where the mistakes in the code were. He even added that the anonymous developer once remarked that he’d been working on it for seven months and it just abruptly started working, not aware that this was because Lorenzen had been playing the part of the elves to his shoemaker. Eventually Lorenzen understood the code well enough that Atari did indeed let the original developer go, and after seven months on the project, Lorenzen was able to finish it off in 2 kilobytes of cartridge space. For his trouble, Lorenzen was paid a $7,000 bonus for his work on the game.

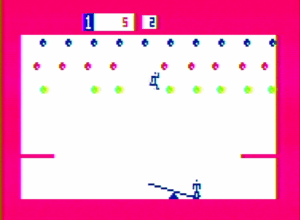

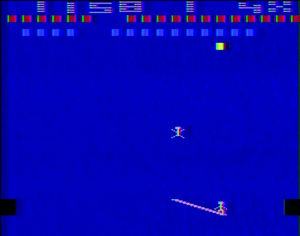

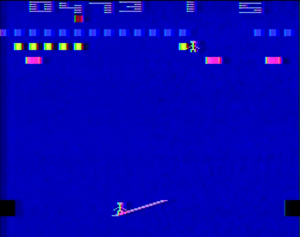

Whatever the development troubles that the game went through, Lorenzen and his mystery collaborator put together an excellent version of Circus for the VCS. A major key difference between this and other versions is that the paddle button can be used to flip the see-saw. This is something of a compromise solution to not having the extended platforms on the side for the clowns to land on and bounce off; while small “platforms” exist, these are really deliberately built out of blank space where the VCS is using a lack of graphical data to perform more calculations than it normally would be. The clown sprites themselves retain the flailing personality and charm of the arcade original, and help make everything feel that much more out of control. The difficulty switches add to this sensation – by flipping it over to a, that player’s clowns will bounce around more quickly than they do in the b position.

The default gametype, known in the manual as Breakout Circus, follows the arcade game’s rules pretty well – balloons only respawn when you clear a row, clowns bounce off the balloons in all directions and clearing the top row gets you an extra life. Other gametypes begin offering up some interesting twists on the formula. The cart includes “Breakthru” Circus modes that call back to the variant of the same name on the VCS Breakout cart, where the clown won’t bounce off the balloons vertically, but only horizontally; this allows players to clear an entire row with a bit more ease than they would in the default gametype. An additional variant keeps the balloons from respawning until all three rows have been cleared, while a final two player variation simply makes two players share the same balloon playfield. Several of these gametypes add in a row of barriers spaced out below the balloons that players have to navigate past in order to hit the balloons. While these can be a bit bothersome to get through given the limited amount of control you have over your clown in the first place, they can actually work out in your favor if the clown begins bouncing off the top side of the barriers and catches onto a series of balloons. It’s a nice twist to add an additional challenge to the game with a minimal amount of new graphical elements needed.

The variations add some longevity to the package, and I can’t overstate how funny it is to see these little stick figures crash and burn when you whiff a catch. Much like the Bally Arcade conversion, the personality of the original comes through, even if this lacks the bells and whistles of its earlier counterpart. If there is something to complain about with this cart, it’s that Circus Atari suffers from a lack of clarity in how to get the clowns to consistently bounce high enough to reach the balloons. Is it number of bounces? Is it where they land on the see-saw? It’s hard to tell for sure, and while this isn’t a unique issue to Atari’s conversion it does seem the most affected by it. The core game is pretty exciting, though, so this is really more of a small gripe than anything major. Indeed, like it’s arcade counterpart, Circus Atari seemed to have wide appeal; the September 1981 issue of Creative Computing looked at the game and noted that it was one of the handful of games from their round up that was well-liked by all of the members of its eclectic review panel. The game’s difficulty was also highlighted in Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games, where it was described as impossible to score more than a few points in the first few games partially due to how hard it is, but also because of how genuinely funny it is when the clowns splat on the ground.

Lorenzen claims that Circus Atari ended up selling 2.7 million copies, though it’s unclear if those numbers are accurate. Jerome Domurat’s internal sales document suggests that Circus Atari sold 148,756 copies in its first year, though subsequent years are cut off in the image we have. These are a drop in the bucket compared to Space Invaders and are slightly below other games available that year such as Night Driver, Air Sea Battle and Breakout, but given the game’s fairly prominent place in newspaper advertising alongside Night Driver it’s clear Circus Atari was in demand. In its later years, that demand seemed pretty consistent, as the game sold just over 85,500 copies between 1986 and 1990. Circus Atari may not have been the prettiest or flashiest game on the shelf, but all indications are that it was a consistently selling one.

This was also Lorenzen’s last VCS game while at Atari, as he volunteered to move over the Atari 8-bit computer department. He did return to the platform after joining Activision, however. He told me that he started his time there working on a clone of Atari’s Lunar Lander arcade game for about four months before deciding it wasn’t really working. Brainstorming his next project, he decided to settle on the Three Little Pigs story, resulting in his released game Oink!. He then started work and subsequently abandoned a ballet-themed game before writing the Pitfall II conversion to the Atari 8-bit and 5200 platforms, which included a unique second quest he devised. Lorenzen’s career then took him to Accolade, where he continued working on a variety of computer games such as Psi 5 and Card Sharks, and assisted with the reverse-engineering effort for the Sega Genesis before leaving video games for a career in selling and installing phone systems, which he found more lucrative and less demanding on his time.

While you’d think Circus as a game concept would have been pretty long in the tooth by 1982, it did not stop North American Philips developer Jim Butler from bringing it to the Odyssey2 platform that year. Oddly licensed in North America as PT Barnum’s Acrobats!, and simply known as Jumping Acrobats in its European Videopac release, this version trades in the paddle seen in other renditions for the Odyssey2’s joystick. While this loses the fine control seen in the Atari and Bally home versions, the size of the sprites and the see-saw, along with the generous nine lives the game gives you, allows this to work well enough to be playable. What really sets this version apart is that it is compatible with the Odyssey2 Voice module, which had just come out about a month before. The Voice is a voice synthesis attachment that plugs into the console’s cartridge port, with its own speaker and volume gauge for the actual voice to come from. This was a little trickier than it sounds on the programming side of things; another Odyssey2 developer, Bob Cheezem, explained that with the storage limitations on the cartridge and how memory was accessed, functionally all the voice clips had to be accessed while the system was doing its vertical retrace between frames. They would have to buffer up the voice sample to play during that window of time and then jump the program back to the portions of memory needed to run the actual game. While he said it wasn’t too technically challenging, it was another thing to keep track of. More difficult was ensuring there was a good enough mix of voice clips; PT Barnum’s Acrobats! features what is known colloquially as the “game show host” preexisting voice samples used in several Odyssey2 games. These play as you pop balloons, lose a life, or leap off the platforms on the side. In all it may not have the variety of the Atari rendition or the fidelity of the Bally version, but the core qualities of Circus are here, and if you were one of the one million households with an Odyssey2 instead of a VCS, this was a good alternative.

Exidy went out of business in the 1990s, and in 2007 Kauffman announced that several of the company’s early games, including Circus, would be available for free, non-commercial usage. Thus, while other companies – largely in Japan – have produced and sold new renditions of the game, the original version of Circus has moved away from the retail rerelease realm in favor of the world of open-source arcade emulation. But the Circus Atari home version has continued to see reissues on modern compilations, and some years ago a homebrew conversion, Super Circus Atariage, was even written for the Atari 7800 platform that uses the joystick, paddle controllers or even the VCS driving controller. From video game musical soundtracks and on-screen character animation, to early consumer voice synthesis and the emulation scene, the unexpected legacy of a title about launching panicky people at balloons continues to weave its way through the world of video games, even today.

Sources:

Mike Lorenzen, interview with the author, Dec. 7 2023 & Dec. 15 2023

Bob Ogdon, interview with the author, Aug. 17, 2020

Bob Cheezem, interview with the author, Aug. 20 2019

Inside Gaming: Meet Bob Ogdon, The Man Behind the Wizard, Arnie Katz, Electronic Games, May 1982

Once Upon Atari, Howard Scott Warshaw, 2003

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

New Games for the Atari Video Computer System, David Ahl, Creative Computing, September 1981

Ferg’s notes from his interview with Mike Lorenzen, 2600 Game-by-Game Podcast, 2013 (shared with me in 2020)

The Ultimate (so far) History of Exidy, Part 1, Keith Smith, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com, May 19 2013

The Ultimate (so far) History of Exidy, Part 2, Keith Smith, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com, May 24 2013

The Ultimate (so far) History of Exidy, Part 3, Keith Smith, allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com, June 4 2013

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, 2016 (unpublished manuscript)

The Lost Turntable, for insight into YMO’s history

Pitfall II’s Secret Sequel, Peer Schneider, IGN.com, Sept. 23, 2023

New Games for the Atari Video Computer System, Creative Computing, September 1981

Weekly Television Digest, Oct. 3 1977, Dec. 19, 1977, Nov. 27 1978

Bally Again Shipping Programmable Games, Merchandising, May 1978

Atari VCS Games Roundup, Martha Koppin, Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games, December 1983

Release date sources:

Circus Atari, July 1981 (Atari VCS) – Source: Chicago Heights Star, June 29 1980; New York Daily News, July 31, 1980; Post Crescent, July 31 1980; Westport News, July 25 1980

Clowns/Brickyard, November 1978 (Bally Arcade) – Source: Baltimore Sun, November 5 1978

P.T. Barnum’s Acrobats!, October 1982 (Odyssey2) – Source: Computer Entertainer, October 1982