It’s been over a year, but Atari has returned to the world of sports with the company’s take on plain old, windmill-free golf. You may recall that the company had published a version of Miniature Golf in March of 1979 seemingly based on an unreleased arcade game. Golf, based on the regular version of the sport, is substantially different in just about every aspect, and feels like a better realized, more functional game all around… just not one that necessarily moves the video golf genre forward a whole lot owing to its console-oriented origins.

Modern golf dates back to 1500s Scotland and involves golfers using a variety of wood and iron clubs to hit a small ball across a course and into a small cup. Every shot adds a point to the score; the goal is to have the lowest score possible at the end of the game. The sport is focused on navigating unique courses and accounting for wind direction, the force and angle of a swing, and physics, making for an interesting challenge to translate to the digital realm. Certainly there have been many attempts over the decades – some absolute masterpieces, and some a bit more rudimentary. The earliest golf games appear to have been written for DEC’s PDP computers in 1970: the first, known as FOCAL GOLF came from Gilbert Fair at DEC’s Northbrook, Illinois office, and is a remarkably feature rich, with nine holes built into the program, instructions for designing your own courses that you can navigate as a back nine or as a complete 18 hole course, and an element of randomness that will impact your swings so that it never plays out quite the same way twice. The other PDP title, PLAY GOLF WITH ARNOLD PALMER, comes from David Cutler of Lake Michigan College in Benton Harbor, Michigan, and has you playing caddy to famed golfer himself, choosing his clubs for him while he manages the actual swings. Both of these programs use ASCII characters to display the course, and appear quite sophisticated for their time. Unsurprisingly, a text-based version appears in David Ahl’s 101 BASIC Computer Games book published in 1973, where you type in the strength of your swing and what club you’re using. This was likely the most widespread golfing program through the rest of the 1970s and into the ’80s. And if you were fortunate enough to have an Apple II in 1979, you could even try out Pro Golf 1 by Jim Wells, which even featured some low-resolution graphics, though mechanically it was very similar to the earlier, text-based games.

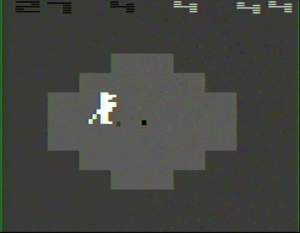

But the next big step forward for digital versions of the game came along that same year, as Magnavox released Computer Golf! for the Odyssey2. This take really defines, mechanically speaking, how a golf game could be done on a home console at the time. Your golfer can trudge around each course, their club always pointing toward the ball. Pushing the button will cause them to begin a clockwise wind-up; the longer you hold it, the more powerful the shot, though if you hold it too long it becomes uncontrolled and will move a random distance. The ball’s angle is determined by the angle of the golfer, and once you make it to the green, the game changes angle to an up-close shot, allowing you to putt it in. It’s a surprisingly elegant piece of game design given how little there was to go on before it, and while each course is little more than a different arrangement of trees and fairway, it’s still pretty fun. The game even features your golfer throwing a little tantrum when they hit a tree. Knock it into the “rough” outside the fairway and the ball stops, forcing you to knock it back in. Sam Overton’s game was praised as an innovative and groundbreaking game in the pages of the Video and Electronic Games magazines, even winning one an Arcade Awards for best solitaire game. With this degree of admiration, it’s unsurprising that Computer Golf! would become the initial template for future games in the genre… Atari’s VCS title in particular.

Atari’s Golf comes to us from Michael Lorenzen, who detailed its development in a 2023 issue of Retro Gamer and a subsequent interview with myself. Lorenzen had an extensive background with computers by 1979, when he was hired into Atari. A student of San Jose State University with a fascination with electronics, Lorenzen took to computer programming while there and even bought himself a Processor Technology Sol-20 microcomputer, which he wired into the university’s computer network to also function as a terminal to its larger minicomputers. Purchasing an Atari VCS near Christmas 1978 to tinker with, Lorenzen eventually figured out what all the components within were, and managed to wire it to his Sol-20 so start modifying game code from the cartridges to see how it worked. After about three months of this, he called Atari asking if they had any programming manuals he could purchase to learn how to make his own games, eventually getting transferred to George Simcock, the then-director of consumer software development. Simcock let him know that those were proprietary, but asked Lorenzen to come by to chat alongside Larry Kaplan, David Crane, Alan Miller and Larry Kaplan, where they picked his brain on how he managed to pull together proprietary information. Ultimately Simcock extended a job offer for when Lorenzen graduated in a couple months, which they made good on after he ran into Miller at the Consumer Electronics Show that summer to remind them about it.

Apprenticing under Alan Miller until he left to co-found Activision after a couple months, Lorenzen said he was able to get input from him and other veteran VCS developers like Crane and Kaplan to get a head start on the VCS hardware, remarking that he and Crane bonded over their mutual love of reverse-engineering technology and hardware. While he doesn’t recall them asking him to join them when they left Atari to form Activision, he did note he wouldn’t have taken them up on it if they had at the time; he did eventually leave Atari for Activision, where he wrote the Three Little Pigs-themed Oink!

Lorenzen had just started at Atari when his manager asked him to go to a specific store to try out the Computer Golf! demonstration setup they had and then implement that as closely as possible on the VCS. While he felt that doing so was surely immoral, if not illegal, he was assured that this was a normal thing to do. After playing the game for a few hours and making mental notes, he felt like he wanted to do an “enhanced” version of what Overton had accomplished.

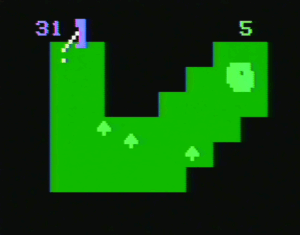

Much like Computer Golf!, you have the same overhead perspective and the same mechanics for the angle and power to your swings. The game even zooms in on the green when your ball makes it there, just as in the Odyssey2 game. Lorenzen added in more obstacles to his version, however: sand traps and water hazards appear here, allowing for more complex course design. Knock the ball into a sand trap, and not only is it difficult to see, but your shots will not send it far at all Knock it into a water hazard, and your score is penalized, with two points being added for your swing instead of one. The difficulty switches adjust what happens if the ball is knocked off the fairway into the rough. On the B difficulty, the ball simply stops, and that’s that, similar to the Odyssey2 original. On A, the ball will enter the rough and become invisible, requiring the golfer to try and find it based on where the club is facing while getting very little distance off each hit. It’s a nice little wrinkle to try and keep things competitive; though once you get the hang of your shots it isn’t too difficult to keep the ball on the fairway. This idea of wandering around the rough looking for your ball came from personal experience. While he was not a golfer himself, Lorenzen remarked that his father was an enthusiast, and that he would join him just for the walks and to look for lost golf balls in the rough, earning anywhere between a penny to a dime from his dad depending on the brand. Atari’s Golf gives players nine holes in the course and an option for two players, with markers at the top of the screen showing your scores, the hole number and each hole’s “par,” or target number of swings.

Lorenzen said Golf took about six or seven months to write, with him pulling 100 hour weeks regularly to complete it. The last six weeks of that stretch were basically focused on him reducing the size of the program from 4 kilobytes to two. Being effectively a clone of Magnavox’s game, it’s a fairly small evolution forward in design, but it plays well. The mechanics seen in this cartridge don’t directly translate to any future golf games, but as the second-ever home console golfing game, it’s arguable that it didn’t need to reinvent the wheel too much to be worth a look; it just had to bring the solid gameplay of Magnavox’s take to the far more popular VCS platform.

Golf also marks one of the early VCS covers from artist Steve Hendricks, who had spent his first two years at Atari working in the coin-op division. In remarks published in Retro Gamer, Hendricks said it was his first cover piece done in the montage style that Cliff Spohn had established as Atari’s “house style” for its VCS titles. He wound up painting the cover twice, as he was dissatisfied with how the original version turned out.

While held back by the 2 kilobyte cartridge size in terms of content, there was an effort to hack Golf to create a full 18-hole course in 2019 that unfortunately was never finished; the programmer working on the hack passed away in 2021, leaving his project incomplete as of this writing. Still, the course from the retail game provides a good mix of challenges on each hole, and while it may not be as robust as one would hope, given the program sizes at the time nine holes wasn’t unusual.

Atari would not have the last word on golf games among its cohort of game consoles or even that year, as only a few months later Mattel’s Intellivision would bring a big step forward in the evolution of the genre. The Intellivision would actually be the home of two different golf games, but the first, PGA Golf, would begin hitting stores around December 1980. Developed by APh Consulting, PGA Golf follows Mattel’s previously released sports games NFL Football, NBA Basketball and Major League Baseball by aiming for complexity and realism over producing a simple, arcade-style game. In this case, players are allowed to select their clubs – a return to form from the earlier computer versions of golf – with each number on the keypad assigned to a different club. The Intellivision disc is used to select your shooting angle in one of its 16 directions. The side buttons are split up into long, medium and short distances – to shoot, you push one of them to begin your swing, and then push it again to determine the angle of your shot; the closer to the bottom of the swing you are, the straighter the shot will be. Pushing the button early makes you hook the shot to the left, while pushing late will cause it to slice right; pushing nothing will produce a random angle. You can’t put any spin on the ball, but given the sheer amount of options for a 1980 golf game, coupled with the clever take on the actual swing, it’s hard to consider this anything but a masterwork for its time.

The game even simulates the effectiveness of certain clubs for specific situations; for example, some of the irons tend to pop the ball up higher upon connecting with it, and getting around trees requires using the right club to avoid the branches; the manual has a few handy charts showing how each club causes the ball to travel and how far. Naturally, something like the sand wedge is ideal for getting out of sand traps, while irons are more useful in the rough than the woods. If you hit the ball into the water, you can either choose to play it at the shoreline or have it reset back at the starting point, albeit with the player no longer getting to use their driver for that initial shot. And unlike most other Intellivision sports games, there’s no difficulty options: PGA Golf takes all its challenge from the core game itself. If it fumbles anywhere, it’s the putting: The tiny size of the hole makes it very difficult to line up your shot correctly and get the ball in. But even this isn’t that big a deal considering how much this game gets right with very little to look to for guidance. It also suffers from a lack of randomization, as while tree locations shuffle around, the courses themselves remain the same… but this is true of other contemporary golfing games, so it isn’t that big of a ding against PGA Golf.

The game features nine holes with the full set of golfing obstacles – water hazards, sand traps, trees, rough patches and the green itself. While not nearly as straightforward to play as the Atari and Magnavox games, Mattel’s game is still easy enough to play that even a non-golfing enthusiast can have a good time. Mattel seemed to see it as a major step ahead of Atari’s Golf, making it a major focus of its 1981 advertising. While one could argue that Atari’s Football and Home Run carts simply offered a different, more arcade-y play experience than Mattel’s attempt at realism, Golf has no such claim against PGA Golf – the latter simply does most everything better. Atari’s game still has the zoom-in on the green, which makes putting far more interesting and intuitive, but beyond that PGA Golf simply felt like a “next generation” game compared to Atari’s. That said, PGA Golf appears to be on more of the niche side of Mattel’s sports library. According to a mid-1983 internal memo, PGA Golf sold to retailers approximately 33 thousand copies in its brief 1980 retail run before selling 150 and 157 thousand in 1981 and 1982, respectively. By mid-83 the game had sold to stores 364,100 units – a far cry from the sizable numbers Major League Baseball, NFL Football and NBA Basketball pulled.

PGA Golf was itself surpassed by its follow up, Chip Shot: Super Pro Golf. Chip Shot was developed from the ground up in the system’s twilight years before being published in 1987 by INTV Corporation, and was something of a labor of love by designer Steve Ettinger. Ettinger was an avid golfer at the time, which is why when developer Realtime Associates received an assignment to spruce up the original Mattel golf game with some new features – an approach taken by INTV for several other sports games – he instead offered to create an entirely new game from the ground up, with a slew of modern features. The most prominent change is that this version utilizes a defined swing gauge, a mechanic popularized with Nintendo’s 1984 Golf cartridge for the Famicom that debuted in the west the following year. The original PGA Golf’s swing system was sort of a half-step towards the swing gauge, but Chip Shot fully embraces what was by 1987 a standard feature in golfing video games. In an interview with YouTuber Papa Pete, Ettinger explained that he was inspired by Nintendo’s Vs. Golf arcade version of the Famicom cartridge, as well as by the limitations of the nine hole 1980 Intellivision game to produce a much bigger game.

Chip Shot also features five full 18-hole courses, with 99 holes to choose from to build out a custom course; Ettinger explained that it was really just 33 holes that were then flipped on the X axis for another 33 and on both the X and Y axes for the final 33. Additionally, however, he brought back the randomized tree locations from PGA Golf, and the new mechanics, notably a wind factor for each shot, putting green location and inclines on the green, were also randomized. Chip Shot also includes practice modes for both general driving and putting. Even the graphics were a real high point for the platform, as Chip Shot uses a full 16 kilobyte cartridge (as opposed to PGA Golf’s four kilobytes), giving graphics artist Connie Goldman plenty of space to make the game shine. She and Ettinger even used photographs of pro golfer Jack Nicklaus to animate the swing. This is easily one of the finest video golfing experiences on a game system of the Intellivision’s vintage; more broadly, it’s one of the best of its day when it came out. The press seems to agree with that assessment; the Computer Entertainer newsletter gave it a glowing review in its August 1987 edition – Chip Shot’s four stars even surpass the 3 and a half stars given to The Legend of Zelda in the same issue!

And it goes without saying that the Bally Professional Arcade had its share of golf games written, published and sold by its enthusiast base using the various versions of BASIC the system had. Mike Maslowski wrote the earliest, Arcade Golf, which was published in the Cursor newsletter in July 1980, right around the time Atari’s Golf cart was coming out. This took the unusual step of including BASIC code to calibrate the controller’s paddle-esque knob, which was used to control the angle of your swings. The idea here was that you’d mark on the controller where the center point is on the knob and keep that in mind when making your shots. Honestly it’s a pretty good take on the game, combining aspects of the graphical versions seen on consoles to that point with the club selection and numerical force entry of the text-based computer versions. It even includes wind as a factor for your shots. Another game, simply titled Golf, was written by Bob Hensel and published by the Arcadian in February 1981 and is actually far less intuitive then the one written by Mike Maslowski, having you choose your angle from a preordained set and providing very poor visual cues as to what, exactly, is your target. This version was revisited by Ken Lill, as program development within the enthusiast community was rather iterative and communal, with members taking code and modifying it to either create something new or improve an existing program. In this case, Lill used the Blue RAM memory expansion for the Bally to produce a much more sophisticated take on the game, with a mobile golfer, a ball that goes “above the ground,” and even a special hole-in-one visual that Lill tells me no one he’s aware of has ever actually achieved (this includes the author of this piece). There was a final golf game seemingly programmed later in the decade on the platform called Pro Golf, another Blue RAM version that brings in the now familiar double-tap power bar seen in Nintendo’s Golf. There’s a bit of a mystery around how this game was distributed – the tape that the version online stems from came from a fellow named Dave Carson, but he never told anyone how he heard about it and got a copy in the first place – by 1988, no Professional Arcade newsletters were still running, though fans who had met through the platform did tend to keep in touch; Carson was also known for being a BBS regular who reportedly could find anything through them, so it is likely that he knew author Henry Sopko in some capacity and got the game that way. In any event, Carson passed it to Mike White, a Bally fan who was behind the BASICarts; these were essentially BASIC programs that booted up from cartridges. He produced a single BASICart of Pro Golf and sold it to Ken Lill, who in turn has included the game on his Bally multicarts since. Both of these memory expanded games play quite well, and are all the more impressive given the platform’s age and the limitations of the BASIC languages that they work around. White suggested that all of these games were built in some part over their predecessors going all the way back to Maslowski’s title, which may be a reason why there is such a through-line of design improvements.

Atari, on the other hand, never revisited the sport past Lorenzen’s take on it on the VCS. The company sold just under 9,000 copies of the game in 1987 and 1988 – the biggest years for the VCS during the Atari Corporation era – but never published an updated version to supplant it as they did with sports like basketball or baseball. This is something of a shame, as updated golf games on the Intellivision and the Professional Arcade showed that there were new tricks one could eke out of limited hardware designed in the late 1970s. But for 1980, Golf is a perfectly fine conversion of the sport. It doesn’t do a whole lot to build on the foundation laid down in Magnavox’s release the year before, and it is effectively surpassed by Mattel’s game a few months down the line, but even if it doesn’t do anything new, it’s not too far above par.

Sources:

Mike Lorenzen, interview with the author, Dec. 7 2023 & Dec. 15 2023

The Making of Golf, Retro Gamer #252, November 2023

Ken Lill, interview with the author, Jan. 14 2020

Mike White, correspondence with the author, November 2019-May 2020

Arcade Golf, Cursor, Vol. 1 Issue 6, July 1980

Golf, Arcadian, Vol. 3 Issue 4, February 1981

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

Cartridge Shipment Memo, Mattel Electronics dated Nov. 30, 1983

Chip Shot: Super Pro Golf, blueskyrangers.com

FOCAL GOLF PROGRAM FOR THE PDP-8 (8K) COMPUTER, Gilbert Fair, DECUS Program Library, Jan. 1 1970

PLAY GOLF WITH ARNOLD PALMER, David Cutler, DECUS Program Library, Aug. 21 1970

The Arcade Awards, Electronic Games, Winter 1981

Tour the Video Links, Electronic Games, July 1982

Arcade Alley, Video, May 1980; November 1981

101 BASIC Computer Games, David Ahl, 1973

Shamelessly Trying Again… Golf Hack, Anyone?, Atariage.com

Intellivision: How a Videogame System Battled Atari and Almost Bankrupted Barbie, Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman, 2024

Papa Pete Live Interview with Blue Sky Ranger Steve Ettinger, June 18 2024

Release Date Sources:

Golf, July 1980 (Atari VCS) – Source: Chicago Heights Star, June 29 1980; New York Daily News, July 31, 1980; Post Crescent, July 31 1980; Westport News, July 25 1980

FOCAL Golf, Jan. 1, 1970 – Source: DECUS listing (see above)

Play Golf with Arnold Palmer, Aug. 21 1970 – Source: DECUS listing (see above)

Pro Golf 1, Summer/Fall 1979 – Source: Softape Summer/Fall 1979 catalog

Computer Golf!, July 1979 – Source: Salina Journal, July 25 1979; Paris News, October 25 1979; Alamogordo Daily News, March 20 1980

PGA Golf, December 1980 (Intellivision) – Source: Dover Times Reporter, November 27 1980; Los Angeles Times, November 9 1980; Blue Sky Rangers game list; St. Joseph Herald Palladium, December 24 1980

Arcade Golf, July 1980 (Bally BASIC) – Source: Cursor, July 1980

Golf, February 1981 (Bally BASIC) – Source: Arcadian, February 1981

Arcade Golf, November 1983 (Blue RAM BASIC) – Source: Astro-bugs, November 1983; Arcadian, Aug. 15 1986

Chip Shot: Super Pro Golf, July 1987 – Source: Computer Entertainer, August 1987;Blue Sky Rangers game list

Pro Golf, August 1988? (Blue RAM BASIC) – Source: Mike White’s Astrocade tape software document (download link)