When the Atari VCS launched in 1977, there were two racing games that went out alongside it. Indy 500 is almost without question the better of the two, and features some of the best racing action on the platform in its lengthy life.

The overhead perspective and game mechanics seen in Indy 500 were pioneered by Atari in its March 1974 single-player arcade game Gran Trak 10, the company’s first true racing game. Gran Trak 10 was inspired by a pen-and-paper game called Racetrack published in the January 1973 edition of Scientific American. Developer Steve Mayer felt like the calculations used in that game to determine the movement of cars along a track could be used in a video game. Larry Emmons did the circuit design, and eventually Ron Milner came on board to help them finish the game, which included several firsts for arcade games: it’s the first game to use a ROM chip to store sprite data rather than hard-coding characters on the board. It’s the first game to use a dedicated monitor rather than repurposing a television, and it’s the first game to use interlaced video for its display. Essentially, the game will draw all the odd-numbered scanlines first and then circle back around for the even-numbered scanlines, which allowed for higher resolution and smoother animation. Despite all these innovations, Gran Trak 10’s production was a debacle, with manufacturing problems, pricing problems and expensive parts. The issues were great enough that even though the game sold around 10,000 units, Atari still took a hit in 1974 that put them $600,000 in the red. The game was nevertheless reportedly successful for arcade operators.

Gran Trak 10 was something of a predecessor to three more racing games that Indy 500 would be based on: Indy 800, Indy 4 and Crash ‘N Score. The first two arcade machines, clearly named in homage for the annual Indianapolis 500 race, are incredibly similar, but the key difference is the number of players: April 1975 release Indy 800 allows up to eight players to compete against each other simultaneously, while the May 1976 version Indy 4 whittles that down to four players. In either game, players take hold of steering wheels and try to maneuver their car around a track, completing laps. Crashing or going off-road will slow a driver down immensely until they can get back on the road. The screen is in the center of the arcade console, with mirrors showcasing the action to passersby. The massive Indy machines featured separate circuit boards to manage each individual car, and used color displays to help differentiate who is driving which car. They also took up a lot of floor space and aren’t terribly easy to come by today, due in part to smaller production runs and annoyance with Atari by distributors after it reneged on a promise to only produce 200 Indy 800 machines.

Luckily, a two-player rendition of these games exists on the Atari VCS. Indy 500, also released as Race by Sears, doesn’t quite capture the multiplayer chaos that its arcade siblings bring with them. But the finest Atari VCS arc ade ports never pull every element of the arcade game together – rather, the developers look at the game, figure out the most important or notable aspects of the arcade original, and determine what they can cut and what needs to remain for the game to be recognizably what it is. It’s an interpretive style that started with Combat, and really shines here. In the case of Indy 500, programmer Ed Riddle recognized the VCS’s limits and reduced the number of players to two, and swapped out the gigantic arcade tracks in favor of something that would be legible on any size screen – not just the 25 inch arcade monitor used on Indy 800 and Indy 4.

ade ports never pull every element of the arcade game together – rather, the developers look at the game, figure out the most important or notable aspects of the arcade original, and determine what they can cut and what needs to remain for the game to be recognizably what it is. It’s an interpretive style that started with Combat, and really shines here. In the case of Indy 500, programmer Ed Riddle recognized the VCS’s limits and reduced the number of players to two, and swapped out the gigantic arcade tracks in favor of something that would be legible on any size screen – not just the 25 inch arcade monitor used on Indy 800 and Indy 4.

Notably, Indy 500 is also the only commercially released VCS game to use the driving controllers, which were packed in with the game. The driving controllers use a rotary encoder, instead of a potentiometer like the paddle controllers. These offer full 360 degree rotation, and provide each player with 16 angles of precision on which way they want to turn their car. Riddle tried to get the game to work with the standard paddle controllers, but since the pots eventually will hit their edge in either direction, it just wouldn’t work. Riddle assigned the sole controller button as the accelerator, with the top speed available adjusted with the difficulty switches on the game console.

In interviews, Riddle has said when he was hired in 1977, he had been instructed to program a game even though he had never done any programming before – his background was in engineering and building phone switching boxes prior to joining Atari. Larry Wagner got him started by giving him documentation; more notably, Wagner provided him with the code he had already done for an Indy conversion in an early Combat prototype. Riddle learned to program, and using Wagner’s work as a base started coming up with different game variations to include on the cart.

In interviews, Riddle has said when he was hired in 1977, he had been instructed to program a game even though he had never done any programming before – his background was in engineering and building phone switching boxes prior to joining Atari. Larry Wagner got him started by giving him documentation; more notably, Wagner provided him with the code he had already done for an Indy conversion in an early Combat prototype. Riddle learned to program, and using Wagner’s work as a base started coming up with different game variations to include on the cart.

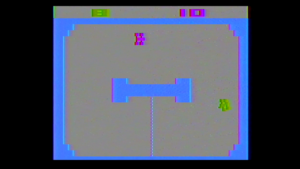

Riddle decided on four major game variants. The first, Race Car, allows players to either race the clock in a one-player time trial mode or go head to head in a race to finish 25 laps on either a grand prix track or the “Devil’s Elbow” route. These are pretty standard racing games that best carry over the arcade game experiences.

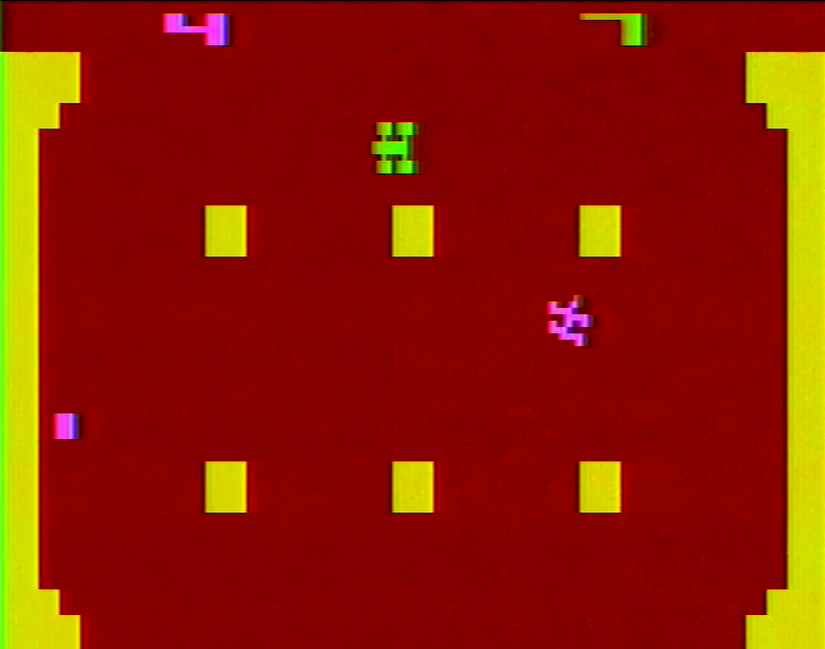

In “Crash n Score,” players maneuver around one of two tracks trying to ram into a white square to score points, either in a timed game or a first-to-50 points version. The game is surprisingly hectic, as players veer wildly to hit the square or knock their opponent off course at the last moment. This is the gametype based on Atari’s self-same October 1975 arcade game Crash ‘N Score, where players compete to run over flags to score points in an enclosed arena, and by all indications it is a very close conversion.

The “Tag” variant reuses the Crash n Score tracks, starting one driver off as “it” scoring a point for every second they are blinking. Once the other player rams them, they become it and begin racking up points, with a goal of reaching 99 points first. While tag games date back to the original Magnavox Odyssey, Indy 500 puts together one of the more interesting renditions thanks to the playfields each car has to maneuver around. For the driver being pursued, the dirt patches provide a handy obstacle to slow down their opponent, while the pursuer can try and trap their target by leading them to crash into a wall, slowing down and giving them a chance to tag.

Finally, Riddle included an Ice Race variant, which included an early example of what have become known as ice physics. In those gametypes, the cars will skid around loosely when turning, lacking the traction a clear road would provide. Much like the standard race gametypes, these are either played in a time trial version or in a two-player race. Riddle considered learning to do the ice physics one of his favorite experiences while developing the game, and it’s pretty impressive to see your car careening off course if you try to take a turn at too high a speed or too sharp an angle in a 1977 release. Riddle has said that “Ice Race” came about from him maxing out the angle, speed and road slipperiness parameters that the game uses in every gametype to produce something pretty fun.

Finally, Riddle included an Ice Race variant, which included an early example of what have become known as ice physics. In those gametypes, the cars will skid around loosely when turning, lacking the traction a clear road would provide. Much like the standard race gametypes, these are either played in a time trial version or in a two-player race. Riddle considered learning to do the ice physics one of his favorite experiences while developing the game, and it’s pretty impressive to see your car careening off course if you try to take a turn at too high a speed or too sharp an angle in a 1977 release. Riddle has said that “Ice Race” came about from him maxing out the angle, speed and road slipperiness parameters that the game uses in every gametype to produce something pretty fun.

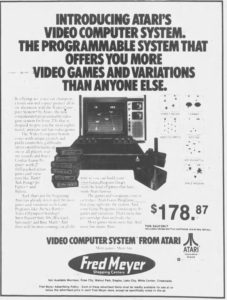

Because it came packed in with the two driving controllers, Indy 500 sold for double the price of other VCS games at launch. Indy 500 sold for $39.95, a steep jump above the $19.95 all other VCS games were on the market for. But without the driving controllers to act as a steering wheel, Indy 500 doesn’t work very well. Atari revisited that style of game with 1986’s Super Sprint arcade game, which received its own Atari VCS port in 1989 near the end of the console’s commercial life under the title Sprintmaster. While Sprintmaster is a prettier game with power ups and more complex tracks, steering with the standard Atari joystick is more difficult and far less intuitive than simply turning the driving controller knob. It’s actually kind of unfortunate, as the VCS played host to a number of racing games, and many of them could have been adapted effectively to the driving controller; on the other hand, in the years since Indy 500 came out, we’ve seen many times over that if a controller or accessory isn’t packed in with a game system from the get-go it’s much less likely to see a whole lot of support, simply because the potential sales base is going to be that much smaller. So in a sense, Indy 500 also pioneered the genre of “good games that require you to dig out specific controllers”.

On the flip side, while the driving controller makes it a breeze to steer, it’s not as comfortable to use as one would want. Since players constantly have to hold down the button to keep their speed up, it’s incredibly easy to develop a hand cramp after even one race.

Indy 500 wasn’t the only racing game of its type on the home market. The RCA Studio II played host to Speedway, an Indy 500-style game written by Joyce Weisbecker. Like Indy 500, Speedway came out in 1977 and featured two blocks representing cars racing around the singular track to reach nine laps. Without the rotary controls that Indy 500 uses, the two cars can only move in four cardinal directions around the track, gradually picking up speed until they crash into a wall or each other. Maneuvering using the Studio II’s keypads is surprisingly tricky to master, and even the manual suggests positioning your hands in a specific way to limit hitting the wrong keys. Coincidentally, a Tag game also by Weisbecker was included on the cart as well. Speedway/Tag isn’t as complete a package as Indy 500, but it’s an interesting piece of convergent evolution and highlights the gulf between what Atari was doing and its early competitors. The game also came out relatively late in the Studio II’s short life, seemingly not reaching stores until around November 1977. This was also Weisbecker’s final Studio II project, though she would be contracted to write a few more games for RCA’s COSMAC VIP computer system before moving into actuarial work. This all said, in a way Speedway also resembles a racing game written by Toni Robbi for RCA’s FRED prototype computer around April 30, 1973, called Spot Speedway. In this game the player’s spot must navigate one of two winding tracks as quickly as possible without crashing, using the machine’s hex keyboard to accelerate, decelerate and turn through the course. Based on documentation at the Hagley Library and Museum, Weisbecker did indeed play this version, and did quite well at it too.

Before leaving Atari, Riddle worked on a follow up to Indy 500 called “Roach Wars,” where cockroaches ran around the ground firing projectiles at each other behind them. The setting would have been household environments such as a kitchen, and Riddle said to allow for projectiles to be fired this game used the joystick – left and right turned your roach, up accelerated, and the button fired your butt bombs. Roach Wars went unreleased amid concerns that people have negative connotations with cockroaches, and a prototype has unfortunately never turned up. Riddle would leave Atari shortly afterwards, not being much of a video gamer, though he did work on breadboarding a 3D Pong-style game that did work, though Atari management felt it would be too tiring for people to actually play with the filter glasses.

Even without that Roach Wars pseudo-sequel, Indy 500 still has managed to hold a following today. The website Atariage has two distinct hacks of the game featuring a variety of new tracks for fans to cruise around, and hackers have added driving controller support to Sprintmaster too. And for modern racing game fans, the game’s driving controllers really are the ancestors to the steering wheel controllers that started springing up on home systems with the Colecovision. Future racing games on the platform may have added power ups or shifted perspectives, but Indy 500, for all its little flaws, is one of the standouts of the VCS’s 1977 lineup.

Sources:

2600 Game by Game Podcast: Indy 500 and Street Racer, May 2013

Ed Riddle, interview with Scott Stilphen, 2017

Joyce Weisbecker, interview with the author, February 8 2020

The Joe Weisbecker papers, Hagley Library and Museum

Larry Wagner, interview with the author, August 25 2018

They Create Worlds, Alex Smith, 186-189, 2019

Atari: Business is Fun, Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, 247-250, 2012

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, 2016 (unpublished manuscript)

Fixing Gran Trak 10, Ed Fries, June 14 2017

Release Date Sources:

Indy 500, September 1977: Merchandising, June 1977

Washington Post, September 16 1977

Corvallis Gazette Times, October 29 1977

Speedway/Tag, November 1977: RCA press release November 15, 1977