It’s undeniable that Atari initially made its name with Pong. This simple two-player take on a tennis game was an incredible arcade success for the company, with competing clone machines popping up in the years following its 1972 debut. Even the earliest years of the home console market saw an array of Pong clones – itself a clone of the tennis game on the original Magnavox Odyssey. There is just one problem with Pong: It’s a two-player game. If you don’t have someone to play with, you’re not going to spend money on it.

There are two ways to tackle this problem, and Atari essentially covered them both. The first is the solution seen in the 1977 VCS game Video Olympics, where developer Joe Decuir programmed a simple computer opponent for players to compete against. This required actually having the memory available and the processing power to actually create your digital foe, and in the mid-1970s these were both in short supply. The other option was to reimagine Pong as a single player game.

This had been done in a couple ways by other developers. Ramtek’s Howell Ivy developed Clean Sweep in 1974, a simple take on the concept where the player bounces a ball off a paddle to try and collect all the dots on screen. Midway released its own single-player paddle game, called TV Flipper, early in 1975; this seemingly was a licensed release of a follow-up to Clean Sweep developed by Ramtek called Knockout that could be considered the progenitor of the “paddle pinball” subgenre of video games. Exidy released a nearly identical game at about the same time called TV Pinball, though the relationship is uncertain. Clean Sweep, TV Pinball and TV Flipper are more mashups of Pong and pinball machines, as the goal is to hit targets across the screen with a paddle and ball, but they are some early examples of developers trying to make a single-player Pong game work.

Back at Atari, Nolan Bushnell and Steve Bristow came up with their own idea for a solution, seemingly based on the racquetball craze of the 1970s. What if, instead of volleying a ball back and forth with another player, you were bouncing a ball off a wall, destroying it, and then trying to catch the ball to do it over again? The history is a bit spotty here, but according to internal memos this initial proposal for “Clean Sweep with a closed field that you knock out” came up around January 1975 during an off-site brainstorming retreat.

This all happened right on the cusp of microprocessors becoming the preferred way to design arcade machines, so complex, transistor-transistor logic game design ruled the day. Atari, interested in reducing the number of logic chips they needed to get for their games – and thus, the production cost – offered a bonus for keeping the number of chips used below 120. None of Atari’s engineers were interested in taking up the task, however, as they considered (with good reason) ball and paddle games to be dead on the market.

Atari game technician Steve Jobs – yes, the same guy who went on to co-found Apple Computers – volunteered to design this single-player pong game, interested in the bonus to help finance his regular trips to Oregon. Bushnell and Bristow, expecting little but realizing Jobs knew some talented friends, gave him the assignment. Jobs then turned around and convinced his friend and future Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak to help him, promising him half the $700 base pay for the work. Jobs, it was later learned, never mentioned the rest of the rather sizable potential bonus to Wozniak. Wozniak wasn’t a stranger to games – reportedly designing his own Pong game with some minor visual enhancements in only 28 logic chips – and was therefore a sensible choice to help Jobs. Over the course of a grueling four-day period, Wozniak successfully designed a Breakout board that used about 42 logic chips, which Jobs wire-wrapped into a prototype. For context, most TTL games at the time were using upwards of 100 logic chips.

Wozniak’s design for the game was missing key features, such as sound and coin control, and also dropped on-screen scoring in lieu of an LED panel, but it worked as a starting point. This all likely occurred within the first few months of 1975, because Wozniak mentions working on a “Breakthrough” game in an April 1975 Homebrew Computer Club newsletter. This could be a reference to this prototype, though I can’t say for certain – to quote the Simpsons’ Nelson Muntz, records from that era are spotty at best. In any case, even though some of Wozniak’s shortcuts resulted in a design too complicated for Atari’s own testing processes and lacked those key features a usable product would need, because the bonus offer didn’t specify it had to be producible, Jobs got a $5,000 bonus.

This is where the timeline gets murky again. From February on, Atari memos mention a game called “Brick” being in development and expected to have a working prototype by April, initially listed right under the Clean Sweep game idea. Later on, another game, entitled Breakthrough, is location tested in July before being shelved; this may or may not be the same game as Brick and what we know as Breakout today. It’s speculative, but we do know a group of disgruntled Atari designers illegally swiped several Atari game ideas and designs and started their own company, Fun Games, around this time. Fun Games was active only briefly before a lawsuit from Atari shut it down, but the company released a particular game at some point after November 1975 called “Take Seven.” This was largely a collection of Pong clones in a single machine, but one of the options, called Bust Out, was essentially just sideways Breakout; depending on the release timing it could have been taken from development materials within Atari or just as a clone of Breakout itself. Development on a brick-breaking paddle game at Atari seemingly took a hit, but the company wasn’t done with the concept yet.

Towards the end of 1975, Gary Waters of Cyan Engineering was tapped to go back to the Breakout project, redo Wozniak’s version of the hardware, and finish the game. He did so, using a more standard Atari PCB layout that relied on about 100 logic chips. His final version fixed several glitches in Wozniak’s design and added the on-screen scoring, coin mechanism control and audio that the prototype was missing. He also added a two-player option in the process. This game, dubbed Breakout, debuted in May 1976, and quickly became Atari’s most popular arcade machine up until 1979’s Asteroids. In its first year, Atari sold between 11-15,000 units domestically – an incredible number of cabinets for the time.

The game was also a global hit: Atari rewarded their West German distributor, Lowen Automaten, a “platinum” unit in 1977 for outstanding sales. But Japan proved to be the most influential market in the long run. Atari entered the Japanese market in 1973 using Nakamura Manufacturing (better known by the name Namco), owned by Masaya Nakamura, as a distributor. Atari sold its Japanese division to Nakamura in 1974 amidst a cash crunch caused by the collapse of the ball-and-paddle market and the debacle around Gran Trak 10 that put Atari $600,000 in the red. With the medal game fad fading out in Japan, coin operators in the country saw video games as a lucrative replacement. Breakout proved to be a huge success, and Nakamura was unable to keep with demand, leaving an opening for other companies, such as Taito and Universal, to make unlicensed clones of the game. After he was unable to get Atari to ship him more units, and facing unwanted pressure from yakuza gangs offering to deal with his competition for a cut of his profits, Nakamura broke his distribution contract with Atari and started making his own Breakout units. Companies from Namco itself to competitors like Nintendo were soon putting their own twists on the Breakout formula, though it would be Taito that would inadvertently find the biggest success.

Japan’s love for Breakout would lead directly to the country’s first true homegrown global hit. Taito’s Tomohiro Nishikado was heavily inspired by Breakout, noting in his biography by Florent Gorges that despite looking outdated and seemingly playing like the outdated Clean Sweep, Breakout was a significantly more fun experience than that older game. Taito would begin producing its own Breakout machines in tabletop cabinets – essentially tables with a game screen in them and controls under the surface – under the name TT Block, popularizing the game for cafes and other locations upright machines wouldn’t work in. Nishikado himself determined that games didn’t need to be realistic to be a hit based on Breakout’s success, and using its design as a starting point, replaced the paddle with a tank firing up at the sky at targets, and swapping out the bricks with moving alien creatures that could fire back. And so Breakout became Space Invaders, a very different experience based off the same basic concept – much like the relationship between Breakout and Clean Sweep. Space Invaders would be so successful that it would lead to the “Invader Boom” in Japan – and to a lesser extent, overseas – where the game was a fad unto itself; more broadly it’s release is frequently cited as the starting point for the “Golden Age” of arcade video games.

With this global arcade hit and a successful launch of their own home Pong unit in 1975, Atari management saw an opportunity to get Breakout into homes too. The company’s first home version was included on their 1977 dedicated

home console Video Pinball, alongside their own take on a pinball-pong mashup and a proper video pinball game. Creative Computing reviewed the device in July 1978, and David Ahl remarked there that Breakout was undoubtedly the most popular game on the system. It plays very closely to the arcade game, despite squishing down the playfield to fit a standard TV, and the game options allow players to adjust the starting size of the paddle and the number of balls they have to work with. Weekly Television Digest reported that Atari sold around 510,000 dedicated consoles in 1977, a number that includes Video Pinball, Ultra Pong and Stunt Cycle; given that Video Pinball is a much easier game to come across today, one can infer that Breakout likely sold quite a few units that holiday season. Around the same time that Video Pinball debuted the VCS started making its way onto store shelves as well, and unsurprisingly, Atari wanted to bring Breakout to its programmable machine as well.

The task of bringing Breakout to the VCS was one that two programmers were interested in and available to do: Brad Stewart and Ian Shepherd. To decide who got the job, they had an actual Breakout competition using the arcade machine – Stewart ended up clearing the screen and got the ball into a loop, while Shepherd ended up missing the ball entirely. Stewart got the job and got to work.

Stewart said he initially had problems working with the system’s TIA display chip, which he found had a steep learning curve. Joe Decuir – who developed the VCS version of Pong, Video Olympics – offered Stewart some advice on how he would try implementing the game. This caused things to click for Stewart, who said in an interview that the rest of the development was relatively straightforward.

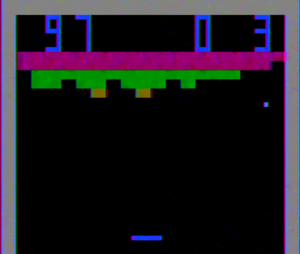

Breakout’s default mode on the VCS is a straightforward port of the arcade game. You clear the bricks out from the wall by bouncing around a ball with your paddle, though there are two key differences from the arcade version that make this an easier task: there are only six rows of bricks for the home version, as opposed to the arcade’s eight rows, and the number of lives has been increased from three to five for the VCS version. Like the arcade, the ball speeds up once it hits some of the higher bricks, and your paddle will be reduced in size once the ball reaches the top of the screen. Like the arcade version, a second wall appears once you finish the first one; clearing that second wall will end the game, leaving the player with a maximum possible score of 864.

Stewart’s alternate game options are where Breakout gets interesting. There are three major variants of Breakout on the cartridge: normal, arcade style Breakout, which we’ve covered already; Timed Breakout, where players must try to remove the two walls as quickly as possible as a clock counts the seconds used; and Breakthru, where the ball will simply smash on through every brick on its trajectory before hitting a wall or the top of the screen and returning back down. Additionally, each of these major variants has four ways to play: an invisible wall mode, where you can only see the bricks when you hit one; Catch, where you can hold the button on the paddle controller to hold the ball as it hits, though it retains its momentum and angle once you let go; Steerable, which allows you to influence the ball’s directional velocity by spinning the paddle; and finally, there’s plain old Breakout. Finally, taking full advantage of the paddle controllers, Stewart included options to play every one of these gametypes with 2, 3 or 4 players; while a two player game will simply alternate whose turn it is like in the arcade machine, playing with three or four players will divide everyone into two teams of one or two players, with teammates splitting up which side of the screen they can move around in. As an added option to tweak the game, moving the difficulty switches to “A” will reduce the size of the paddles.

Stewart’s alternate game options are where Breakout gets interesting. There are three major variants of Breakout on the cartridge: normal, arcade style Breakout, which we’ve covered already; Timed Breakout, where players must try to remove the two walls as quickly as possible as a clock counts the seconds used; and Breakthru, where the ball will simply smash on through every brick on its trajectory before hitting a wall or the top of the screen and returning back down. Additionally, each of these major variants has four ways to play: an invisible wall mode, where you can only see the bricks when you hit one; Catch, where you can hold the button on the paddle controller to hold the ball as it hits, though it retains its momentum and angle once you let go; Steerable, which allows you to influence the ball’s directional velocity by spinning the paddle; and finally, there’s plain old Breakout. Finally, taking full advantage of the paddle controllers, Stewart included options to play every one of these gametypes with 2, 3 or 4 players; while a two player game will simply alternate whose turn it is like in the arcade machine, playing with three or four players will divide everyone into two teams of one or two players, with teammates splitting up which side of the screen they can move around in. As an added option to tweak the game, moving the difficulty switches to “A” will reduce the size of the paddles.

This makes for a pretty complete package of options for what was originally a pretty simple game. Standard Breakout is a fun enough game, though Timed Breakout really seems more for expert players. Breakthru is where I  feel the cartridge really shines, as it results in a fast-paced game where the ball is speeding along practically from the first volley. The three lesser variants are fairly basic, but both the steerable ball and the catch gametypes are a huge boon to avoiding that maddening situation where one block is left and you just. can’t. hit it. The invisible wall is a bit of a stinker unless you’re really good at directing your shots, but it is also disappointing that there’s no way to double or triple up these lesser options. Even so, Breakout is easily the best game we’ve seen so far in 1978, and is one of the most fondly remembered games of that era of VCS development for a good reason.

feel the cartridge really shines, as it results in a fast-paced game where the ball is speeding along practically from the first volley. The three lesser variants are fairly basic, but both the steerable ball and the catch gametypes are a huge boon to avoiding that maddening situation where one block is left and you just. can’t. hit it. The invisible wall is a bit of a stinker unless you’re really good at directing your shots, but it is also disappointing that there’s no way to double or triple up these lesser options. Even so, Breakout is easily the best game we’ve seen so far in 1978, and is one of the most fondly remembered games of that era of VCS development for a good reason.

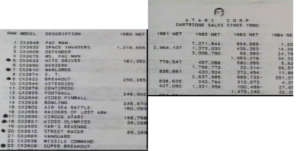

Reviews at the time were high on the cart, especially the Breakthru gametype. In the summer 1979 issue of Video Magazine, Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz said that the home cartridge was a “must” own for its speed and angle changes, noting that Breakthru in particular was addictive and great for tournaments, due to how quick rounds would go. The game also was incredibly popular; an August 1981 Video magazine review of the Atari 400 computer notes that Breakout was one of the best-selling VCS carts of its day, only recently eclipsed in popularity by Space Invaders. A memo owned by

the late Atari developer Jerome Domurat used in part as B-roll in Howard Scott Warshaw’s Once Upon Atari documentary series indicates it was the 9th best-selling VCS game overall since 1980, though the screenshot cuts off the parts that indicate the full time frame. From the portions visible, Atari tracked about 1,650,336 copies sold to retailers between 1980 and 1983, with potentially another 4,000 in 1984. Breakout ended up being a steady seller under the later Atari Corporation VCS run as well, selling roughly 28,000 copies between 1986 and 1988 – not at all shabby for an early port of an even older arcade game.

Breakout was a big enough of a success in arcades that nearly all of Atari’s early competitors had their own take on the game, though some turned out decidedly better than others. The first one out the door was Fairchild’s Pinball Challenge cartridge, which despite the name is just Breakout. The basic premise is that you have 7 balls to try and

destroy as many bricks and walls as you can. To make up for the fact that the system doesn’t have paddle controls, the paddle can be sped up or slowed down by pushing the controller forward or backward while moving; it is also, frankly, huge, and thus harder to whiff with. Like Atari’s there’s a variety of gametypes in here, allowing you to adjust the size of the paddle, the speed of the ball, alternate control of the paddle between two players, play cooperatively with each player tackling moving left or right, or, most interestingly, play an offense-defense version where the second player controls a blocker paddle trying to protect the wall. The invisible wall also makes an appearance here. It’s not as good as Atari’s version, but it’s not at all bad. As an aside, this was developed by Rick Maurer before he went to Atari and created the VCS version of Space Invaders, mirroring in a sense the link between Breakout and Space Invaders in Japan.

Bally had a version on their dual-game Professional Arcade cartridge, Brickyard/Clowns. This version is a bit odd – the ball actually has momentum that can adjust the speed and direction its moving in, giving it a very unique flavor of all the Breakout clones out there. Then-Dave Nutting Associates developer Bob Ogdon said that these kinds of physics were nothing more than calculating the velocity and speed of the object as it bounced off another, a piece of “college physics.” While they may not have had the formal rights to Breakout itself, Ogdon spoke highly of the teamwork that the folks at DNA had when making games for the Bally Arcade. The staff would often pay each other to help find ways to compress code or add new features to their games, and Dave Nutting himself would provide hands-on feedback. The authorship of the game is a little unclear however. While in a 1982 Electronic Games interview Ogdon called Brickyard/Clowns his first project, in a 2020 interview with the author he said that he recalls someone else was “in charge” on Brickyard/Clowns with him helping out, which was a common practice at DNA. The Professional Arcade does feature a spinner on the controller, so moving the paddle quickly and accurately is as breezy as it is on the VCS. The game has options to adjust ball speed and paddle size, but otherwise plays very much like Breakout with some decay on your shots.

APF released a clone in 1978 for their MP1000 called Brickdown, which turns Breakout on its side. It allows players to adjust the number of wall layers and ball speed, though you are still stuck using a standard digital joystick to move the paddle. Again, it’s not bad, but without the sensitivity of a paddle Breakout loses something in the translation.

Jumping ahead a couple years, Magnavox brought out its own clone, Blockout/Breakdown for the Odyssey2. What sets this version apart from others is that the player is competing against either another player or the computer, who is trying to repair the wall as it gets destroyed using little “demons” that grab bricks from the side of the screen before placing them in any empty spaces. Blockout is a standard Breakout game otherwise, while Breakdown follows the Atari Breakthru ruleset, allowing the first player to plow through the bricks.

Mattel even developed its own Breakout clone, Brickout, for the Intellivision, though it went unreleased until the 1998 Intellivision Lives computer compilation. Originally intended to be part of the Triple Action cartridge, the game was axed out of concerns that Atari might file a lawsuit against them. The game, which involves walls slowly coming down towards the player, was reportedly popular among the programmers internally. And in 1982, the console known in the US as the Arcadia 2001 featured Breakaway, a clone with a variety of options from the original VCS port including invisible bricks, differing paddle sizes, catching the ball and Breakthru. The console doesn’t feature paddles, but allows you to shift your speed by pushing one of the keypad buttons.

Notably, Wozniak developed a Breakout clone for the Apple II using its BASIC language interpreter early on in the machine’s life, and spent time making sure that the computer would be capable enough to run his game during the design phase. While it is turned on its side, Break Out for the Apple II plays remarkably well with the system’s paddle controllers – or even its analog joysticks.

And Atari would revisit the Breakout concept a few more times. In 1978 the company released a sequel to arcades called Super Breakout, taking advantage of newly available microprocessors to introduce a variety of twists on the format, such as multiball settings or walls that steadily drop down the screen. Super Breakout would see its own console ports for the VCS and the 5200 a few years later, along with a computer port to the Atari 8-bit line. While the VCS version of Super Breakout looks nicer than its predecessor, it has a completely different set of gametypes and only works with two players. This means Breakout isn’t made obsolete by its successor, and likely explains why the game continued to be sold for so many years on the VCS.

Much later in the VCS’s lifespan, Atari Corporation published another take on the game, Off the Wall, which featured power ups but didn’t use the paddle controllers, to its detriment. This was likely a response to Taito’s August 1986 release Arkanoid, which was essentially Breakout with different brick patterns, power ups, and the occasional enemy as an obstacle. According to a design document, Off the Wall was originally known as Zip’n Zap, and would have optionally used paddle controls; it’s unclear why the feature was cut but conceivably it was a space issue.

The Breakout concept continues to live on; while Atari hasn’t really touched it since 1996’s Breakout 2000, other developers have kept it alive through new Arkanoid games and even indie titles such as Shatter. For a game that no designer wanted to work on in the first place, the idea of bashing bricks with a ball and paddle has proved to be an impressively long-lived one.

Sources:

The Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Papers, Strong Museum of Play

A Breakout Story, Ethan Johnson, December 29 2018

They Create Worlds, Alex Smith, 2019

Atari: Business is Fun, Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, 2012

All in Color for a Quarter, Keith Smith, unpublished manuscript, 2016

The Man Who Created Space Invaders, Florent Gorges, 2018

Video, Summer 1979, August 1981

Homebrew Computer Club newsletter, April 1975

Weekly Television Digest, April 10 1978

Atari Coin Connection, April 1977, May 1977

Creative Computing, July/August 1978

Electronic Games, May 1982

Atari History Timelines, Michael Current

Atari Corp. 2600 Sales figures, 1986-1990

Once Upon Atari, Howard Scott Warshaw, 2003

Bob Ogdon, interview with the author, August 17 2020

Brad Stewart, interview with Scott Stilphen, 2001

John Vifian, interview with Scott Stilphen, 2014